Flavius Josephus and the Archaeological Evidence for Caesarea Maritima

Those who share an interest in the exploration of the world of antiquity know how common it is to make interpretations on the basis of extremely small amounts of information which, in turn, may have been derived from a very small number of sources. This puts a significant burden on the reliability and accuracy of our principal sources, the literary record and archaeology. Sometimes these two sources present a view of antiquity that can be quite at odds with each other. It is, therefore, assuring to an interpretation when we find compatibility between these two windows to the past.

One occasion of close agreement arises between the archaeological data from Caesarea Maritima and the account given about that harbor-city by 1st century AD author Flavius Josephus. The city achieved fame in its early history due to its association with Herod the Great, its early Christian record, and its relationship with Rome. Importantly, as Josephus recorded information about these associations, he also preserved a description of the city that was located along the coast of Israel about 40 miles north of Tel Aviv. Although Josephus’ account of the city covers only the period through the end of the 1st century AD, the history of the city was lengthy. During its long history it experienced occupation by multiple successive cultures before its abandonment in the middle to late 13th century. Here, however, our consideration of the city is restricted to the beginning era of its existence: from the end of the 1st century BC up to the time of Josephus at the end of the 1st century AD.

If scholars seem to pay great attention to what Josephus records about Caesarea, much of this is because his literary works are our single best source for the history of the city during the Herodian period up to the end at the 1st century AD.1 Thus, we are deeply indebted to the description that Josephus has recorded about Caesarea in his works.2 Because Josephus is such a critical source for the history of Judea, scholars have consequently heavily evaluated his works. The result has been the production of an extensive bibliography.3 This bibliography reveals how scholars have received Josephus with a mixture of praise and censure. He is clearly praised for preserving significant and important information about ancient Judea. He has not escaped criticism, however, for his method of narrating certain historical and political events. A few examples serve as an illustration. In recent times Isaiah Press has praised Josephus for his description of the geography of Palestine.4 The praise continues with Magen Broshi5 who notes that there is substantial accuracy and precision in Josephus when comparisons are made with archaeological data. However, observations by others question numerous views offered by Josephus and he is criticized for his descriptions of Judea. In agreement with Press and Broshi, Zeev Safrai praises Josephus for the accuracy of some of his reporting, but also notes that Josephus could make errors in describing the land of Judea.6 On the other hand, Louis H. Feldman remarks that in spite of the access that Josephus had to well-known and precise Roman military records, he made some glaring errors in recording distances and measurements.7 He adds that even though Josephus had been a military general of a country that he claimed to know well (i.e. his homeland of Judea), “there is a mixture of accuracy and inconsistency” in his writings. Feldman concludes that by the time Josephus had completed his description of the three most important archaeological sites in Israel, Caesarea, Jerusalem, and Masada, he had “…emerged with a good, though hardly a perfect, score.”8

What we will note below, as we consider Josephus’ account of Caesarea, is that despite the criticisms that have been leveled against him, his description of the city illustrates significant harmony with what archaeological excavations have recovered about the city’s urban appearance. In the past Josephus’ description was accepted with limited credence and attention. However, as a result of extensive excavations during recent years, an abundance of archaeological evidence has been recovered at Caesarea that confirms Josephus’ description of the city as an important harbor-city in Judea.9 Thus, for example, our view of the city’s role as a link in the trading network along the eastern Mediterranean has changed. Most scholars now recognize the fact that the harbor of Caesarea “…did not maintain its nautical prominence continuously.”10 However, they also acknowledge, as ceramic and archaeological evidence suggests, that even into the 9th and 11th centuries there continued to be considerable activity in Caesarea under Islamic occupation.11 Evidence suggests that during this latter period of the city a wealthy class survived,12 as well as a robust regional trade.13 After the Moslem conquests had taken place it appears that in Caesarea there was not a cataclysmic failure of agriculture production but rather a period of ‘progressive decline’,14 until its final collapse.15

More to our interest, during the first century of its existence, there is now archaeological evidence that the city’s trading activities were much stronger than previously believed, not only in local and regional trade but also in long distance commerce. In this regard, the ceramic evidence from the 1st century indicates greatly increased trading activities in contrast to the trading experiences of its predecessor in the area, the town of Straton’s Tower.16 Pottery from this century shows that through its harbor passed goods from Portugal, Spain, central Italy, the Aegean area, North Africa, central Palestine and the Negev, supporting the view that Caesarea was an important transshipment point throughout the Mediterranean area.17

While medieval sources demonstrate that a certain prosperity and beauty of the city survived into the 13th century,18 the abandonment, destruction, and decay of Caesarea inevitably arrived. Gradually, in the centuries that followed its final abandonment and destruction, the architectural features that defined the city disappeared under the onslaught of time, nature, and human exploitation.

Now, as archaeologists have returned over the last few decades to investigate the remains of the city, their primary guide is Josephus. As a Jewish priest, military officer and historian, Josephus preserved descriptions of the city and much helpful information about historical episodes that the city experienced in its connection with Jewish history. He wrote some eighty years after the time of Herod the Great who, as the king of Judea, had given the orders to construct the harbor of Sebastos and the city of Caesarea and saw the completion of the city somewhere between 13 and 10 BC. By the time the construction was completed, and certainly by the time that Josephus wrote, Caesarea was an imposing city. Josephus was clearly impressed with the city and on several occasions he noted the city’s size, beauty and magnificence. His praise of the city’s architectural features included, at the minimum, its huge harbor, its theater and amphitheater, its sophisticated sewer system, its great temple to Augustus and Rome, and its other urban structures.19

Today, it is true, the greater part of the visible architectural structures of Caesarea belong mostly to historical times subsequent to that of Josephus. In the eras after Josephus, the Byzantine, Islamic and Crusader cultures often expressed their strong presence in the city by constructing their own buildings directly over previous structures. However, through the efforts of marine archaeologists working in the depths of the harbor area and from the efforts of terrestrial archeologists, a growing number of cultural artifacts and architectural features are being exposed which belong to the Herodian and early Roman city that Josephus describes. These discoveries testify to a limited but important ‘inventory’ of architectural and urban features, some of which were recorded by Josephus. While not all of the structures of the Herodian city specifically described by Josephus have been precisely located, previous discoveries seem to portend that even more revelations are forthcoming which will continue the confirmation of Josephus’ description of the city.

Importantly, past archaeological discoveries support an increasing confidence in Josephus’ description of Caesarea and testify that he was indeed quite familiar with the architectural appearance of the city. As our principal literary source, scholars have long recognized the ‘archaeological survey’ that Josephus made about Caesarea as worthy of attention. Now, as archaeological discoveries increasingly agree with Josephus’ account of the city, there has been an enhanced awareness to even the smallest reference that Josephus has made about the urban appearance of the city.

In general terms, which are more fully commented on below, the principal details of the city described by Josephus relate to the foundation and elaboration of a city that was constructed by Herod on the site of a pre-existing coastal town called Straton’s Tower. When Caesarea was completed, it had harbors (havens), temples, arches, streets, several palaces, a theater and amphitheater, and other unnamed public buildings.20 Until recent times, nearly the only thing we had as true testament for the existence of the city was his description. For centuries the physical evidence for Caesarea was almost totally hidden from view beneath the coastal sands or the waves of the Mediterranean. Now, however, archaeology has made very important progress toward revealing the city.

Josephus relates that the city came into being and immediately became important because of the ambitions of Herod.21 Herod had observed that along the coast there was an older and ‘much decayed’ Hellenistic town of Straton’s Tower. As he considered the town, he came to the conclusion that the older town was situated in an important position. Straton’s Tower had been built perhaps as far back as the 3rd century but, despite its dilapidated condition, Herod recognized that it was in a strategic geographical and geological location. Certainly, one factor in this awareness was that just off shore, along much of the shoreline where the city was located, there were geological outcroppings or ‘reefs’ that offered important initial protection from the ill effects of storms at sea.22 Although the geological outcroppings in the sea would not be situated precisely where he would establish the harbor of his town, Josephus emphasizes Herod’s apperception that the old town of Straton’s Tower occupied a most favorable position between Joppa and Dora.23 Furthermore, the geographical location of the site as a whole that was now held by Herod was a geographical outlet of the cross-country roads.

After Herod had evaluated the location of Straton’s Tower and its potential benefits and advantages, he made the decision to build a new city in the location and approached its construction with a dedicated fervor. Indeed, Josephus relates that Herod was most “liberal” and “magnanimous” in the disposal of his wealth in building the city and that he constructed the city in a “glorious manner” with a harbor that literally “over came nature.”24 The city, as Josephus describes it, was built all of fine quality white building stone and was to serve as a “fortress for the whole nation.” However, in order to complete the city, Josephus relates that Herod imported building materials. Now, marine archaeologists have discovered materials within the harbor, including timber and concrete made of pozzolana sand, which have Italian origins and confirm that Herod imported building materials to construct his city. As further elaborated below, upon the completion of the city Herod dedicated it to Rome and Caesar Augustus in order to demonstrate his deep appreciation to his two powerful patrons.25

There seems little doubt today that Herod was very generous with his expenditures on the new city. This is dramatically illustrated in what was the true focus of the city, its great harbor. We also know that he approached constructing the city in a rational and resolute fashion because, as any good ‘city-builder,’ Josephus relates that Herod had a master plan.26 That a plan did exist has become evident through the gradual exposure of the regular orthogonal design of the city. Over the years numerous sections of streets have been discovered that allow a restoration of the plan of a city that was built on an insulae (city-block) pattern. The organization of the city clearly suggests that a master ‘blue-print’ plan had been utilized. Although most of the Herodian city lies beneath later Byzantine and Crusader Period buildings, these later buildings and streets appear to faithfully follow the plan of the original ‘grid-like’ pattern of the Herodian city. With each successive year, the regular ‘grid-like’ pattern of the city’s streets and the insulae become more clearly defined. By example, the course of the principal north-south street (), as suggested by Josephus, has been successfully determined, along with the course of several east-west streets ().

Decumanus 2 to the W. Photo by Farland Stanley

Some of the streets are either Herodian or are a construction over the original Herodian streets. The exposure of the streets is important because it confirms Josephus’ statement that streets were built at equal distances from one another and ran through the city down to the shore and to the harbor.27

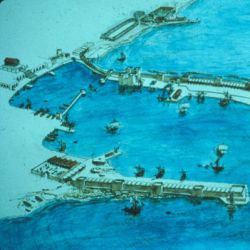

The description of the city’s streets and their orientation toward the shoreline and the harbor draws attention to Josephus’ description of the city’s huge circular harbor (). Clearly, the magnificence of the harbor partly resided in its huge size and design. In fact, and as mentioned above, Josephus says that the harbor was so large and formidable that it literally ‘overcame nature’ as it extended westward into the Mediterranean Sea. This truly seems to have been the case because the foundations for the breakwater, which Josephus calls the (‘first breaker of the waves’), encircles an area some fifty acres in size and served as a safe haven for vessels travelling along the coast. The outer harbor extends from the shoreline and the now silted-up inner harbor, for some 300 meters to the west, before turning to the north for about 500 meters more where the entrance to the harbor was located.28

The harbor is, in actuality, three interconnecting harbors. The outer harbor, which today lies hidden beneath the waves, along with the intermediate and inner harbor, combined to form the principal landing area of the city. In addition, three and perhaps even a total of four subsidiary anchorages are now known to have lain along the coast adjacent and just to the north and south of the inner and outer harbors.29 The inner harbor was situated between a prominent hill on the shore, atop which was located the principal great temple of the city, and the larger outer harbor that extended westward out into the Mediterranean. The basin of the inner harbor is now silted up. However, although it is not mentioned in Josephus, archaeologists have now discovered that the inner harbor had been so well designed that there once was a flushing channel that served as a mechanism by which sea water passed through the harbor and prevented it from being silted.30

Josephus describes the inner and outer harbor complex as larger than the famed harbor of Athens, the Piraeus. It was so huge and magnificent that Herod had even drawn a distinction between the legal and administrative positions of the harbor and the city that, in effect, seems to have set them apart as two separate entities. 31 This is evident in his reference that the city itself was called Caesarea and was dedicated by Herod to the province of Judea. At the same time, the harbor was called Sebaste and was dedicated to the sailors.32

The vastness of the outer harbor was first revealed by an underwater exploration in 1960 known as the Link Expedition.33 Since then, marine archaeologists have continued to demonstrate that Josephus was quite correct in his description of the expanse of the harbor. With the one exception of inaccurately recording the depth of the foundations for the harbor, marine archaeologists have proven that Josephus’ description of the immensity of the harbor is accurate. Accurate, too, is the report that Herod had embellished the grandeur of the harbor with enhancements in the form of other architectural features that accented its appearance as well as added to the functionality of the harbor. Josephus relates that the foundations of the outer harbor, the main mole, were at least two hundred feet wide, before which was a subsidiary breakwater () that served the purpose of helping to break the powerful force of the waves. As described by Raban, the “…was confined as a segmented line of subsidiary breakwater, relatively narrow and not much above the sea level. Being some 20-30 m outside the spinal wall of the mole it would cause breakage of the surge…”34 Approximately one hundred feet of the inner side of the mole were utilized as the foundation that supported a number of structures that were important to the functionality of the harbor. Atop the mole, running along its spine, was an apparent sea wall that lined the outer circle of the harbor. Other structures atop the inner section of the foundations were vaulted chambers that served the dual purpose of storage for trading goods in transit and dwellings for visiting mariners.

Reconstruction of harbor by Avner Raban

Josephus adds that the width of this foundation also allowed for a promenade around the quay of the harbor for those who wanted to take a pleasant walk.35 In sum, marine archaeologists have now demonstrated that Josephus’ description of the harbor is very accurate. Their investigation of the foundations of the outer harbor have revealed that the construction techniques used in building the foundations are remarkably close to what Josephus described.36

One of the more interesting questions about the harbor concerns discussions about a lighthouse (fire tower). A lighthouse is not attested by Josephus, however some archaeologists believe that somewhere there might have been a lighthouse that accented the appearance and functional aspect of the harbor. Despite the lack of attestation, however, its presence would have been important as a place where fire and smoke could be seen for miles at sea as a beacon to the location of the harbor for incoming mariners. Discussions on its location include the supposition that a fire tower could be somewhere at or near the entrance to the outer harbor.37 In this regard Josephus mentions that situated near the entrance of the outer harbor were a total of six statues which stood on either side of the north entrance to the harbor and which rested on underwater foundations. Marine archaeologists have now located the foundations for the towers that supported the statues.38 Josephus recounts that the most beautiful tower was called Drusium, after Drusus the son-in-law of Augustus who prematurely died at a young age. The Drusium was so prominent in the city that some conjecture has been presented that this tower, which Josephus describes as the tallest tower at the harbor, may have been associated with a light tower.39

In conversations with Professor Raban, the suggestion arose about another possible locaton for a light tower. Although difficult to excavate, there is one small area of the southeast side of the foundatons of the outer harbor underlying the location of the present day ‘Citadel Restaurant,’ which may warrant excavations for a possible location of the light tower. Wherever a light tower may have been located exactly, the evidence for the presence of statues seems clear and that they served as both a decorative motif as well as a visible political statement of the closeness that existed between the city and Rome and Augustus.

There are other features relating to the harbor that are not attested in Josephus, but whose importance permits further brief digression. Among these are several newly discovered features, but one of the most important is that, perhaps from the end of the first century the outer harbor fell victim to an underlying geological fault that extended north/south just off the shoreline. This fault caused the outer harbor to sink gradually beneath the waves.40 As a result, over time the superstructure as well as the substructure foundations subsided beneath the waves, allowing a silting process eventually to fill the inner harbor and cause the harbor to succumb to the destructive force of the sea. The existence of the outer harbor is today visible from the air as a dark outline beneath the waves that mark the tumbled and wave-worn remains of the harbor. The huge size of the submerged foundations testifies to the powerful resistance that the offered to the force of the sea and to the support that it gave to the complex of vaulted chambers and promenade that once lined the harbor.

Also not attested by Josephus are two large staircases in the vicinity of the harbor whose discovery added to confirming the urban centrality of Caesarea’s great temple, which will be discussed below. As terrestrial archaeologists began to explore the juncture of the inner harbor with the shoreline, the first of two great staircases was exposed in 1990 through 1995. This was an immense ‘grand staircase,’ sometimes referred to as the ‘western’ staircase.

'Western staircase' to the SE. Mooring stone at far left. Photo by Farland Stanley

The discovery of a second ‘southern’ staircase followed a little later in 1993-1995.

The ‘western staircase’ was a structure that led from the quay of the now land-locked inner harbor up to the top of a fifty-foot high artificially constructed prominence named by archaeologists as the temple platform. Atop this prominence, and overlooking the harbor and the city, was located the huge temple that Herod dedicated to his patrons Rome and Augustus. Although Josephus does not refer to the ‘western staircase,’ it held a particular importance in the city because it was positioned precisely in a location that served as the principal approach to the temple from the harbor. It would be appropriate, therefore, for all individuals arriving into the city by way of the harbor to visit the temple by using the staircase.

As the grand ‘western staircase’ was excavated, it was found not to date to the Herodian era but to the fifth century and the Byzantine period. However, this later staircase rested immediately over a lower structure that has been shown to be the original quay of Herod’s harbor. Today, an original mooring stone remains intact in the quay.41 The large structure that comprises the Byzantine ‘western staircase’ abuts the front or western facade of the temple platform. Most of the facade of the temple platform has not been excavated and thus presents some uncertainty about the design of the actual Herodian staircase that served as an approach up to the great temple. However, without doubt, the Herodian ‘staircase’ is under the later one. Future excavations will be required to confirm its exact design.

In 1993 and 1994, a second staircase of almost equal size to the ‘western staircase’ was excavated on the southern side of the Temple Platform. This staircase turned out to be in line with the principal north-south street of the city (cardo) and the center of the southern side of the Herodian temple foundations.42 This ‘southern’ staircase demonstrates several construction phases that match the several occupational periods of the city.

'Southern staircase' early in excavations looking to the NW. Photo by Farland Stanley

However, the lowest phase reveals that it was originally constructed in the Herodian era. The importance of this staircase is that its alignment with the principal north/south street of the city allowed expeditious and easy access to the Temple Platform from the southern part of the city to the temple. Both staircases serve as important connection points with two of the principal arteries of the city and emphasize the centrality of the temple platform within the city.

Returning now to features of the city that are attested by Josephus, we note his use of the plural to refer to temples within the city. Below we will discuss the largest temple found at Caesarea, but his plural reference to temples raises the suspicion that lesser religious structures existed in the city. In fact, a rich assortment of sculptural fragments of varied Greek deities increases the suspicion that there were other smaller religious structures in the city. However, the numerous statues and fragments of statues found within the city should not necessarily assume a temple for each deity for, as discussed below, despite the religious piety that religious statuary elicited, they were also used for decorative purposes.43

Among the evidence for other smaller religious structures is that which points to religious structures utilized for the imperial cult. The discovery of the famous ‘Pontius Pilate stone’ clearly testifies to the presence somewhere in the city of a small religious building, called a Tiberium. Although the Tiberium is not attested in Josephus, this stone carries an inscription that specifically mentions that Pilate built a structure called a Tiberium. Pilate, whose reputation is well known as one of the early governors of the province of Judea and for his association with the crucifixion of Jesus, dedicated the small religious structure to the ‘genius’ of the emperor Tiberius. Literary references also exist for another and later religious structure called a Hadrianum. Although this structure belongs to a time later than what we are considering here, and although its exact location is not known, an immense statue of the emperor Hadrian has been found which suggests that a Hadrianum did exist.44

The literary references to these imperial cult structures suggest that we might well assume that other similar structures existed in the city that were dedicated to other Roman emperors. In fact, in addition to the adoration of the emperor, we need to keep in mind the presence of a large number of additional sculptural and architectural pieces that have been found in the city. Their presence is witness that many different Greek and Roman deities were welcomed in the city.45 Doubtless, in time there will be archaeological evidence for other smaller temples or religious structures in which the representations of at least some of the more important Greek deities were housed. However, it seems more likely that the majority of the religious statues were displayed along streets within the city. How many statues and temples were displayed at this time? We cannot know for certain. However, a hint that there may have been many is reflected in Josephus’ comments about an uprising that took place in the city among the Jews and Syrians during the procuratorship of Felix. The implication is that the number of Greek statues and temples had reached a sufficient number to reflect an increased Greek character of the city that was unacceptable to the Jewish population and contributed to inciting the Jews to rebellion.46

There is, however, one very large religious structure that is clearly attested by Josephus that emphasizes the close relationship between Caesarea and Rome. This was the temple which Josephus described as built by Herod and dedicated to Rome and Augustus, which both emphasizes the close relationship between Caesarea and Rome and the power of the imperial cult. In recent years excavations have included it among the dramatic discoveries made at Caesarea.47 It was discovered, as Josephus had indicated, in a commanding position in the center of the city overlooking the harbor from atop a high elevation, which is the area designated by archaeologists as the temple platform. Beginning in 1900, and continuing through the 2000 season, archaeologists have exposed much of the foundations for the temple.

Foundations of Herod's temple. Photo by Farland Stanley

These discoveries, and those of column fragments and other architectural fragments, now permit a proposed reconstruction of a large hexastyle temple whose superstructure is estimated to be almost 21 meters in height. The deeply laid foundations, which measure approximately 5 meters in width, define the plan of a temple that was 28.6 meters in overall width and 46.4 meters in length.48 These measurements outline a temple that was clearly one of the largest Roman temples that was built in the Mediterranean world. Unfortunately, almost all indications of the temple’s superstructure were robbed in antiquity for use by succeeding cultures. Nevertheless, the survival of the huge foundations and various tantalizing fragments of the temple testify to the temple’s grandeur.

It was once believed that the temple was made entirely of marble because of Josephus’ reference that the city ‘gleamed’.49 It is now known that the builders of the city utilized local sandstone called kurkar as the principal building material not only for the city, but for the temple as well. Because marble is not indigenous to Israel, in antiquity the importation of sufficient amounts of marble to build the temple, or the city, would have been beyond the wealth of even King Herod. Still, we are confronted with Josephus’ comment about the ‘gleaming’ appearance of the temple.

The first to fully address the construction materials of the temple was Lisa Kahn. Although Josephus specifies that the building material was marble, she proposed other materials and methods that could account for the shining aspect of the temple. She notes that other religious structures Herod constructed in Judea were made of local stones, which included limestone. Among the numerous architectural fragments found on site, Kahn drew attention to several carved fragments of kurkar that probably belonged to the temple.50 These fragments were ‘worked’ kurkar stones whose shapes suggested that they belonged to the frieze of the temple. On some of the frieze stones were preserved a design motif called dentiles which still retained, on some of their interior spaces, a coating of white plaster.51 Here was the first indication that the ‘gleaming’ appearance of the temple, as well as other buildings in the city, could be accounted for by a coating of white plaster or stucco. In 1999 and 2000, archaeologists excavating on the temple platform made important discoveries to confirm this suggestion.

In the excavation seasons of 1999 and 2000 archaeologists found several large thin and curved fragments of white stucco while excavating in trenches on the temple platform adjacent to the southern side of the foundations of the temple. Previously, large sections of column drums made of kurkar had been discovered which revealed that the diameter of each of the temple’s columns was over two meters. The size and curvature of the stucco fragments disclosed that they had indeed served as a stucco coating that encircled the outside of the columns.

On the outside of the stucco were preserved the design of flutes which were intended to imitate the fluting of a marble column.52

Fragment of stucco with flutes. Photo by Farland Stanley

The grandeur of the temple was not only apparent from the outside, but also on its interior. Josephus describes two colossal statues that were housed within the temple; one that represented Augustus and the other that represented Rome. He relates that these two statues were made of gold and that they were comparable in size to the Zeus at Olympia and the Hera of Argos, two famed statues that were fashioned earlier in the fifth century BC by the Greek sculptors Phidias and Polycleitus.53 No remains of these statues have survived, however one coin from the city illustrates what may be depictions of the two colossal statues of Augustus and Rome that were within the temple.54

Josephus relates that Herod also added to the grandeur of the city when he ordered that a magnificent palace be built for himself. This palace has now been discovered and excavated on a promontory to the south of the harbor and adjacent to the city’s theater.55 The palace was extensive in size and elaborate in construction. Its extant ruins clearly indicate that it added significantly to the splendor of the city and helped to distinguish the city as one of the most impressive in the Mediterranean world.

Another impressive structural survivor from the Herodian period is the theater, which Josephus mentioned, situated adjacent to the southeast side of the palace area. It was excavated by a team of Italian archaeologists in the 1950s, and has been restored for modern usage.56 Also adjacent to the palace, and extending to the north from the palace along the shoreline toward the southern side of the inner harbor, is a newly discovered colossal hippodrome.57 The seaside hippodrome, which will be discussed below, is the second hippodrome discovered at Caesarea. The first, which lies about one-half mile to east of the city, has been known for some time, but until 2000 only limited exploration of the site has taken place.

There are, as we have seen above, descriptions made by Josephus for a number of structures in Caesarea that range from subterranean conduits () and sewers () to the city’s great temple, and the harbor.58 We have also noted that there are structures found in the city that are not mentioned by Josephus. In this regard we should also add the discoveries for the remains of storage complexes () in Area CC and LL, which while mostly dating to the post Herodian period do have, in at least one instance, limited evidence for the Herodian period.

The first complex is a series of very well preserved storage vaults which were found in Area C in a part of the city located to the south of the temple platform and the Crusader fortifications which surround the city.

Frontal view of two restored horrea in Area C. Photo by Farland Stanley

In all, this complex consists of four large Roman storage vaults () which date to the post Herodian period. 59 Initially, this complex of storage vaults was entirely covered by sand, which added to the dramatic discovery of Vault I by Robert Bull in 1973 and 1974.60

Roman Mithraeum. Photo by Farland Stanley

Excavations and analysis of ceramics found in vault I show that at the end of the 1st century this vault was converted into a Mithraeum, a religious building used for the worship of the god Mithras. The vault apparently continued to be utilized for this purpose through the mid- to late third century. 61

General view of Area LL looking to SW. Photo by Farland Stanley

In Area LL, a second complex of storage facilities has been found adjacent to the north side of the inner harbor just off the shoreline. Most of what is currently visible relates to a complex of Byzantine warehouses and storage bins. However, as indicated by deep foundations, these Byzantine warehouses and bins were constructed directly over the foundations of structures that appear to date to the Herodian period. Because of the alignment of the walls of the later Byzantine warehouse atop the Herodian foundations, the excavators suggest that the earlier foundations supported a Herodian warehouse.62

Wall of Islamic storage bin (to the left) resting against Herodian foundations in Area LL.5. Photo by Farland Stanley

In conversations with Professor Raban it was suggested that the earlier foundations may be ship sheds because of their nearness to the sea. However, the continuity of usage for storage facilities in this location would appear to have a bearing on understanding the level of usage that carried over to the harbor during the early Byzantine period.

Walls of Byzantine warehouse in Area LL1. Note wall to the right resting on Herodian foundations. Photo by Farland Stanley

Although there is a lack of full or specific description, Josephus also mentions that Caesarea had public buildings. These buildings must include his specific reference to a theater and amphitheater. Some of these buildings were most likely the sites for the games that he described as celebrated in honor of the emperor Augustus.63 While Josephus seems correct about the usage of the theater, until recently there was confusion over his reference to an ‘amphitheater’ that he said was located near the theater.64 For years the site of an amphitheater has been located to the northeast of the temple platform area, and an ‘eastern’ hippodrome has been located on the eastern outskirts of the city. The amphitheater to the northeast has not been excavated and its date of construction is not known. The ‘eastern’ hippodrome, however, which is just now being excavated, apparently dates to a time that follows Josephus. At first, scholars thought that Josephus had confused the location of the amphitheater and that he had mistakenly placed it south of the temple platform area and near the theater. Alternatively, others thought that the erroneous location was due to a scribal error. Now, however, a second huge public structure has been recently excavated to the south of the temple platform area in the very location where Josephus said that the structure existed near the theater. The structure that was discovered is a unique building that was constructed along the shoreline between the southern side of the temple platform and the north side of the promontory on which the palace of King Herod was built. Its location perfectly fits Josephus’ description as a building that could hold a large crowd of people and had a view over the sea.

The structure is rectangular and extends north/south along the shoreline, with a curved southern end and an elevated seating area along its eastern side. At the north end of the structure are located the carceres or starting gates for the chariot races that were held in the structure. The internal measurements of this structure are 265 meters north/south and 50.35 m east/west. The excavators have shown that in its first phase of usage the building was clearly a hippodrome. This could very well be the structure where some of the games and horse races took place that Josephus mentions were sponsored by Herod in honor of Augustus.65 On the other hand, Josephus refers to the structure as an ‘amphitheater’ and not a hippodrome.66 To this may be added one very brief comment by Josephus where he specifically refers to “the great stadium” in Caesarea. Unfortunately, he does not give any indication at all of its location.67

Yosef Porath believes that Josephus’ reference to a stadium at Caesarea is probably a reference to the structure that Josephus also calls an “amphitheater,” which he said was near the theater and palace of Herod.68 The confusion in his description of the structure as a stadium and an amphitheater has now been solved by archaeology. The answer is that the structure, which is a stadium or hippodrome, at some later time in its history, had its length truncated at a point 130 m from the southern end. At this location, a narrow curving wall was built that crossed from the west lateral wall to the east lateral wall. This modification effectively turned the southern one half of the structure into an amphitheater. Thus, to describe its later usage, its excavator Yosef Porath discusses this whole structure as a ‘multiple-purpose building,’ while John H. Humphrey refers to it as a ‘Hippo-Stadium.’ 69

Josephus mentions that the city also included other large and impressive structures, including marketplaces, and ‘sumptuous palaces’ with most elegant interiors.70 At the present time, it is believed that one marketplace may lie just to the north of the temple platform. Excavations have not taken place there, however, to confirm this supposition. The sumptuous palaces, described as possessing ‘elegant interiors,’ likely include the palace of Herod and may also refer to large nearby villas that have not yet been discovered.

One final structure that is not mentioned in Josephus’ description of Caesarea is a city wall. Today large sections of an immense wall, with its large northern entrance and towers, still exist as evidence for a wall that once encircled the city. Despite excavations and study of these structures, scholarly debate continues with no clear resolution as to the date of the wall.71

With the close of this evaluation of Josephus’ description of Caesarea, one deduction becomes apparent. Josephus was remarkably accurate. The precision in the conformity between recent archaeological discoveries and Josephus’ description of Caesarea demonstrates the attentiveness that he gave to recording what he observed and what he learned from sources that he probably had at hand when he wrote. What makes his description even more impressive relates to the chronological gap between the time when Herod built Caesarea and the time of Josephus. During this interim Caesarea had undergone almost a century of embellishment and change. However, whatever the methods of investigation that Josephus used in addition to his power of observation, he was able to divorce himself from the Caesarea of his day and evaluate the city as it was originally fashioned. In doing so, he reported his description in a manner that strongly endorsed Herod as a Jew and a King to whom Josephus carefully ascribed no feature of the city unless the association was clear.

When this evaluation of Josephus began, attention was drawn to the burden that is placed on the reliability and accuracy of our principal sources, the literary record and archaeology. Here, after making a comparison between the description of Caesarea by Josephus and recent archaeological discoveries, we have one of those happy moments when compatibility is demonstrated between our two primary records of antiquity. For a historian who has sometimes been maligned for his descriptions and reports of historical events and places, the description that Josephus gave of Caesarea is remarkably verified by archaeology. Therefore, as it relates to his description of Caesarea, for the accuracy of his report he deserves to receive credit as a historian.

Josephus’ Description of Caesarea (translations by J. P. Oleson and the author, see note 2, below)

Jewish War I. 408-414

(408) He [Herod] noticed a settlement on the coast — it was called Straton’s Tower () — which, although much decayed, because of its favorable location was capable of benefiting from his generosity. He rebuilt the whole city in white marble (), and decorated it with the most splendid palaces, revealing here in particular his natural magnificence.

(409) For the whole coastline between Dor and Joppa, midway between which the city lies, happened to lack a harbour, so that every ship coasting along Phoenicia towards Egypt had to ride out southwest headwinds riding at anchor in the open sea. Even when this wind blows gently, such great waves are stirred up against the reefs that the backwash of the surge makes the sea wild far off shore.

(410) But the King, through a great outlay of money and sustained by his ambition, conquered nature and built a harbour () larger than the Piraeus, encompassing deep-water subsidiary anchorages within it ().

(411) Although the location was generally unfavourable, he contended with the difficulties so well that the strength of the construction () could not be overcome by the sea, and its beauty seemed finished off without impediment . Having calculated the relative size of the harbour () as we have stated, he let down stone blocks () into the sea to a depth of 20 fathoms (ca. 37 m). Most of them were 50 feet long, 9 high, and 10 wide (15.25x2.7x3.05 m), some even larger.

(412) When the submarine foundation () was finished, he then laid out the mole () above sea level, 200 feet across (61.0 m). Of this, a 100-foot portion was built out to break the force of the waves, and consequently was called the breakwater (). The rest supported the stone wall (teichos) that encircled the harbour. At intervals along it were great towers (), the tallest and most magnificent of which was named Drusion, after the stepson of Caesar.

(413) There were numerous vaulted chambers () for the reception () of those entering the harbour, and the whole curving structure in front of them was a wide promenade for those who disembarked. The entrance channel () faced north, for in this region the north wind always brings the clearest skies. At the harbour entrance () there were colossal statues, three on their side, set up on columns. A massively-built tower () supported the columns on the port side of boats entering the harbour: those on the starboard side were supported by two upright blocks of stone yoked together () higher than the tower on the other side.

(414) There were buildings right next to the harbour also built of white marble, and the passageways of the city ran straight towards it, laid out at equal intervals. On a hill directly opposite the harbour entrance channel () stood the temple of Caesar [i.e. Roma and Augustus], set apart by its scale and beauty. In it there was a colossal statue of Caesar, not inferior to the Zeus at Olympia on which it was modeled, and one of the Goddess Roma just like that of Hera at Argos. He dedicated the city to the province, the harbour to the men who sailed in these waters, and the honour of the foundation to Caesarea: he consequently named it Caesarea ()

Jewish Antiquities 15.331-341

(331) Noticing a place on the coast-line very suitable for the foundation of a city — formerly called Straton’s Tower — he undertook a magnificent project () and built the whole city not any old way but with structures of while marble, adorning it as well with very costly palaces and civic buildings.

(332) But the greatest project and that which required the most effort was a harbour protected from the waves (), equal to the Piraeus in size, with quays () and secondary anchorages () inside. The remarkable thing about the construction was that he did not have any local supplies suitable for so great a project, but it was brought to completion with materials imported at enormous expense.

(333) Now this city is situated in Phoenicia, on the coasting route down to Egypt, halfway between Dor and Joppa. These are two little towns directly on the coastline, poor mooring places (), since they lie open to the southwest wind, which constantly sweeps sand up from the sea bottom on to the shore and thus does not offer a smooth landing (). Most of the time merchants must ride unsteadily at anchor off shore.

(334) To correct this drawback in the topography, he laid out a circular harbour () on a scale sufficient to allow large fleets to lie at anchor close to shore, and let down enormous blocks of stone () to a depth of 20 fathoms (ca. 37 m). Most were 50 feet long, not less than 18 feet wide, and 9 feet high (15.25x5.49 x 2.7 m.).

(335) The structure () which he threw up as a barrier against the sea was 200 feet wide. Half of this opposed the breaking waves, warding off the surge breaking there on all sides. Consequently, it was called a breakwater (). [J. P. Oleson, the translator of these passages, notes the two different spellings, and . In my text I use only ].

(336) The rest comprised a stone wall () set at intervals with towers (), the tallest of which, quite a beautiful thing, was called Drusus — taking its name from Drusus, the stepson of Caesar who died young.

(337) A series of vaulted chambers () was built into it for the reception () of sailors, and in front of them a wide, curving quay () encircled the whole harbour, very pleasant for those who wished to stroll around. The entrance () or mouth () was built towards the north, for this wind brings the clearest skies.

(338) The foundations () of the whole encircling wall on the port side of those sailing into the harbour was a tower () built up on a broad base to withstand the water firmly, while on the starboard side were two great stone blocks (), taller than the tower on the opposite side, upright and yoked together ().

(339) A continuous line of buildings finished off with highly polished stone formed a circle around the harbour, and in their midst was a low hill carrying a temple of Caesar visible from afar to those sailing towards the harbour. It contained images of both the Goddess Roman and of Caesar. The city itself is called Caesarea () and is very beautiful both for its materials and its finish.

(340) But the underground conduits () and sewers () received no less attention than the structures built above them. Some of the drains led into the harbour and into the sea at regular intervals, and one transverse branch connected all, so that rainwater and the waste water of the inhabitants was all carried off easily together. And whenever the sea was driven in from off shore, it would flow through the network and purge the whole city of its filth.

(341) In the city he (Herod) built a theater () out of stone () to the south, and behind the harbor an amphitheater (), that had the capacity to hold a great number of men and was situated suitable for a view to the sea. The city was completed in twelve years, and during this time the king did not fail in continuing the work and paying the necessary bills.

1 I wish to express my appreciation to Professor Avner Raban from the University of Haifa for his invaluable advice, guidance and help in preparing this paper. On Josephus as a best source for Caesarea: Tessa Rajak, Josephus: The Historian and His Society. (Duckworth, London 1983) 1.

2 The works of Josephus include the Bellum Judaicum, Antiquitates Judaicae, his Vita, and Contra Apionem. Those most pertinent to this study are the Bellum Judaicum and the Antiquitates Judaicae, designated respectively as BJ and AntJ. At the end of this paper appear the two principal sections of these works that describe the city of Caesarea. The translations for these sections are those of J. P. Oleson in Avner Raban, “Sebastos, the Royal Harbor of Herod at Caesarea Maritima: 20 Years of Underwater Research,” in G. Volpe (ed.), Archeologia Subacquea cone Opera l’Archeologo Storie delle Acque. Edizioni All’insegna del Giglio (Firenze 1998) 217-273. Oleson’s translations appear on pp. 266-269 and are based on the Greek text in the Loeb editions of Thackeray (1927) 192-196 for the Bellum Judaicum and Marcus and Wikgren (1963) 1581-64 for the Antiquitates Judaicae (341). To these translations I have added my own for Antiquitates Judaicae 341.

3 Louis H. Feldman. Josephus: A Supplementary Bibliography. (New York 1986).

4 Isaiah Press, Eretz Israel: A Topographical-Historical Encyclopaedia of Palestine. 4 vols. [English] 1946-1955.

5 Magen Broshi. “The Credibility of Josephus,” Journal of Jewish Studies, 33 (1982): 379-384.

6 Zeev Safrai, “The Description of Eretz-Israel in Josephus’ Works,” [Hebrew] in Collected Papers: Josephus Flavius: Historian of Eretz-Israel in the Hellenistic-Roman Period, Uriel Rappaport, ed. (Jerusalem 1982) 91-115. By example, Safrai criticizes Josephus’ description of Judea in BJ 3.506-520.

7 Louis H. Feldman, “A Selective Critical Bibliography of Josephus,” in Josephus, the Bible and History, Wayne State University Press (Detroit 1989), 435-6.

8 Feldman (above, note 7) 436. Feldman points out that this agrees with the concluding views of Eric M. Meyers, “The Cultural Setting of Galilee: The Case of Regionalism and Early Judaism.” Aufsteig und Niedergang der römischen Welt 2.19.1 (1979) 686-702.

9 Josephus’ general description of the harbor may have some points of argument, but the accuracy was first noted by Avner Raban, “Josephus and the Herodian Harbour of Caesarea” [Hebrew], in Collected Papers (above, note 6) 1-5. The principal archaeological efforts within the last three decades have been through the Joint Expedition to Caesarea Maritima (JECM), the Caesarea Ancient Harbor Project (CAHEP), the Combined Caesarea Expeditions (CCE), and the Israeli Antiquities Authority (IAA). For a helpful history of the archaeological excavations at Caesarea, see Robert Lindley Vann, “Early Travelers and the First Archaeologists,” Caesarea Papers: Straton’s Tower, Herod’s Harbour, and Roman and Byzantine Caesarea, ed. Robert Lindley Vann, JRA, Supplementary Series number 5, [designated as Caesarea Papers] (Ann Arbor, MI 1992) 275-290. See also K.G. Holum “Introduction: History and Archaeology,” Caesarea Maritima: A Retrospective after Two Millennia. Eds. Avner Raban and Kenneth G. Holum, [designated as Retrospective] (E.J. Brill 1996) 359-377, xxvii-xliv. In the same volume see R.R. Stieglitz, “Stratonos Pyrgos — Migdal (ar — Sebastos,” Retrospective, 593-608. For the palace of Herod, see Ehud Netzer, “The Promontory Palace,” 193-207, Kathryn Louise Gleason “Ruler and Spectacle: The Promontory Palace,” 208-227, and Barbara Burrell “Palace to Praetorium: The Romanization of Caesarea,” 228-250.

10 Yossi Mart and Ilana Perecman, “Caesarea: Unique Evidence for Faulting Patterns and Sea Level Fluctuations in the Late Holocene,” Retrospective (above, note 9) 9 and note 21.

11 Moshe Sharon, “Arabic Inscriptions from Caesarea Maritima: A Publication of the Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae,” Retrospective (above, note 9) 401-440. See especially 401.

12 Sharon (above, note 11) Inscription no. 9, 429-30.

13 Yael D. Arnon, “The Islamic and Crusader Pottery (Area I, 1993-94).” In K.G. Holum, A. Raban, and J. Patrich, eds. Caesarea Papers 2: Herod’s Temple, The Provincial Governor’s Praetorium and Granaries, The Later Harbor, A Gold Coin Hoard, and Other Studies. JRA, Supplementary Series Number 35, 1999, [designated as Caesarea Papers 2] 225-229.

14 E. Ashtor, A Social and Economic History of the Near East in the Middle Ages. (London 1976) 55. See Kevin Green, The Archaeology of the Roman Economy. (University of California Press, 1986) 140.

15 Adrian J. Boas, Crusader Archaeology: The Material Culture of the Latin East. (Routledge 2000) 12, 47, 99.

16 Ceramic evidence demonstrates that the trading activity of Straton’s Tower was restricted to the local Palestine area. J. P. Oleson, M. A. Fitzgerald, A.N. Sherwood, and S. E. Sidebotham, The Finds and the Ship. Vol. 2 of The Harbours of Caesarea Maritima: Results of the Caesarea Ancient Harbour Excavation Project 1980-1985, ed. J. P. Oleson, BAR Int. Ser. 594 (Oxford 1994) 20-21; 143-144. Oleson, “Artifactual Evidence for the History of the Harbors” 369-370 and cf. L.I. Levine, Roman Caesarea: An Archaeological Topographical Study, Quedem: Monographs of the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University, no. 2, (Jerusalem 1975) 52-53, 56 n. 115.

17 Jeffery A. Blakely, Caesarea Maritima: The Pottery and Dating of Vault I. (Lewiston, NY 1987) 39-42; 149-150. See especially appendix IV “Petrological and Heavy Mineral Analysis of Selected Amphora Fragments,” 227-248. Analysis of the content of the varied ceramic shipping vessels reveals that among the items shipped were wine, oil, defructum, garum and muria.

18 While its appearance and size would vary over the centuries, varied evidence illustrates that its vitality as a city survived even until the middle of the thirteenth century. In fact, as late as the tenth century, the geographer Muqaddas (AD 947-990) wrote of the bounty and richness of the city and reported that no other city was more beautiful along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean. Muqaqddasî, Ahsan al-Taqâsîm fi Ma?rifiat al-Aqâlîm, ed. M. J. De Goeje (Leiden 1906) 174.

19 BJ 1.411 on “beauty and ornament.”

20 Lee I. Levine, Caesarea Under Roman Rule (Leiden 1975). For a brief history of Straton’s Tower and its relation to Phoenician through Hellenistic history, see 5-14. On the other public buildings, see AntJ 15.331.

21 Robert L. Hohlfelder, “The Changing Fortunes of Caesarea’s Harbours in the Roman Period,” Caesarea Papers (above, note 9) 76-77. Kenneth G. Holum, Robert L. Hohlfelder, Robert J. Bull, and Avner Raban, King Herod’s Dream: Caesarea on the Sea. (New York 1988) 73.

22 Mart and Perecman, Retrospective (above, note 9). On the ‘much decayed city,’ see BJ 1.408.

25 On the importation of building materials: AntJ 15.332 and Raban (above, note 2) 233. John Peter Oleson and Graham Branton, “The technology of King Herod’s harbour,” Caesarea Papers: Straton’s Tower, Herod’s Harbour, and Roman and Byzantine Caesarea. Ed. by Robert Lindley Vann, JRA Supplement no. five (1992), 56ff. On the dedication of the city: AntJ 15.293; BJ 1.414.

27 On the alignment of streets: BJ 1. 414. On the ‘conduits’ and ‘sewers’: AntJ 15.340.

28 On the size of the harbor, see Mart and Perecman (above, note 9) 9 ff. On the inner harbor see Avner Raban, “Sebastos, the Royal Harbor at Caesarea Maritima: A Short-lived Giant,” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 21 (1992) 111-124. For a discussion that the outer harbor began to subside toward the end of the first century, see Raban (above, note 2) 221ff.

29 On the existence of subsidiary harbors, see Robert L. Hohlfelder, “The Changing Fortunes of Caesarea’s Harbours in the Roman Period.” Caesarea Papers (above, note 21) 75.

30 John Peter Oleson and Graham Branton, “The Technology of King Herod’s Harbour,” in Caesarea Papers (above, note 9) 55. Avner Raban, Eduard G. Reinhardt, Matthew McGrath, and Nina Hodge. “The Underwater Excavations, 1993-94,” Caesarea Papers 2 (above, note 13) 153-168. Ron Toueg, “History of the Inner Harbor in Caesarea,” C.M.S. News: University of Haifa Center for Maritime Studies. Report No. 24-25 December 1998, 16-19. The archaeological evidence for the flushing channel consists of the remnants of a sluice or channel along the southern side of the breakwater close to the shoreline where it acted as a de-silting system. The system worked by utilizing the force of either wave action or the slight northward current of the sea that ran along the shore.

31 Dan Barag, “The Legal and Administrative Status of the Port of Sebastos during the Early Roman Period,” Retrospective (above, note 9) 609-614. See especially 613.

33 For a general history of marine archaeology at Caesarea, including the Link Expedition to Israel in 1960, see Robert L. Hohlfelder, “The First Three Decades of Marine Explorations” in Caesarea Papers (above, note 9) 291-294.

34 BJ 1.411; on the and depth of the water, see Raban (above, note 2) 239.

35 BJ 1.411-13; AntJ 15.334-338.

36 Oleson and Branton, “The Technology of King Herod’s Harbour,” Caesarea Papers (above, note 9) 49-67. Raban (above, note 2) 227ff.

37 Robert L. Hohlfelder, “Caesarea’s Master Harbor Builders: Lessons Learned, Lessons Applied?” Retrospective (above, note 9) 85-86. Joseph Patrich, “Urban Space in Caesarea Maritima, Israel,” in Urban Centers and Rural Contexts in Late Antiquity. Thomas S. Burns and John W. Eadie, eds. (Michigan State University Press 2001) 77-110. See 84 and note 40.

38 Hohlfelder, Retrospective (above, note 9) 85 ff.

39 On the statues: AntJ 15.334-338; BJ 1.411-13. On a relationship between the Drusion and a light tower, see Raban (above, note 2) 233 and Patrich (above, note 37) 84.

40 For a helpful summary of the varied early structures found at Caesarea see Patrich (above, note 37) passim. On the subsidence of the harbor, see Avner Raban, (ed.), Harbour Archaeology, Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Ancient Mediterranean Harbours, Caesarea Maritima, 24-28-.6.83, BAR International Series 257 (Oxford 1985) 74-89. Raban (above, note 2) 219, 221ff. Ron Toueg, “History of the Inner Harbor in Caesarea,” C.M.S. News: University of Haifa Center for Maritime Studies. Report No. 24-25 December 1998, 16-19. Mart and Perecman, Retrospective (above, note 10).

41 Farland H. Stanley Jr. “Area I/8,” 40-42, in Avner Raban, Kenneth G. Holum, Jeffrey A. Blakely, The Combined Caesarea Expeditions: Field Report of the 1992 Season, Part I, University of Haifa, the Recanti Center for Maritime Studies, Pub. No. 4, 1993.

42 Farland H. Stanley Jr. “The South Flank of the Temple Platform (Area Z2, 1993-95 excavations),” in Caesarea Papers 2 (above, note 13) 35-40.

43 Patrich (above, note 37) 77-110, 88. Rivka Gersht. “Representations of Deities and the Cults of Caesarea.” in Retrospective (above, note 9) 305-324.

44 Rivka Gersht, “Roman Statuary Used in Byzantine Caesarea,” Retrospective (above, note 9) 391; K.G. Holum, “Hadrian and Caesarea: an episode in the Romanization of Palestine,” Ancient World 23.1 (1992) 51-61.

45 For the cults, see Rivka Gersht, “Representations of Deities and the Cults of Caesarea,” in Retrospective (above, note 9) 305-24. R. Gersht “Roman Copies Discovered in the Land of Israel,” in R. R. Katzoff (ed.), Classical Studies in Honor of David Sohlberg (Ramat Gan 1966) 434-41.

47 Lisa C. Kahn, “King Herod’s Temple of Roma and Augustus at Caesarea Maritima,” Retrospective (above, note 9) 130-145.

48 Holum, “The Temple Platform: Progress Report on the Excavations,” Retrospective (above, note 9) 17-26.

50 Kahn, Retrospective (above, note 9) 131. As early as 1990, Kahn discussed with Kenneth Holum (co-director of the excavations) the possibility that kurkar was the principal building material of the temple and not marble.

51 Kahn, Retrospective (above, note 9) 141.

52 Avner Raban and Kenneth Holum. “The Combined Caesarea Expeditions, 1999 Field Season,” C.M.S. News, University of Haifa Center for Maritime Studies, Report No. 26 December 1999, 11. A field report of the discoveries at Caesarea as of 2000, including the white stucco, is forthcoming. Kenneth G. Holum, Jennifer A. Stabler, and Farland H. Stanley, Jr. “Areas TP and LL in the 2000 Excavation Season,” JRA (Forthcoming). The report is currently available on the official Caesarea Expeditions web page on the internet (http://digcaesarea.org/Documents/2000FieldReport.htm).

54 The coin (see BMC Palestine, p. 238, no.23) is of Agrippa I and dates to AD 43/44. On the reverse of the coin is a depiction of the front of the temple and what may be the statues of Augustus and Roma.

55 Ehud Netzer, “The Promontory Palace,” Retrospective (above, note 9) 193-207; Kathryn Louise Gleason, “Ruler and Spectacle: The Promontory Palace,” Retrospective, 208-227. Patrich (above, note 37) 92.

56 A. Frova, “Excavating the Theatre of Caesarea Maritima-and the Goddess Whom Paul Hated,” Illustrated London News (1964) 524-526.

57 Yosef Porath, “Herod’s ‘Amphitheatre’ at Caesarea: a multipurpose entertainment building,” The Roman and Byzantine Near East: Some Recent Archaeological Research, JRA, Supp. Ser. No. fourteen, 15-27; John H. Humphrey, “Amphitheatrical Hippo-Stadia,” Retrospective (above, note 9) 120-129. Patrich (above, note 37) 92.

58 For the conduits and sewers: AntJ 15.340; for the temple see above notes 47 through 52; for the harbor see above notes 28 through 37.

59 Joseph Patrich, “Warehouses and Granaries in Caesarea Maritima,” Retrospective (above, note 9) 146-176.

60 See Robert Bull and J.A. Blakely, Ch. 2, “Stratigraphy” in Caesarea Maritima, the Pottery and Dating of Vault I: Horreum, Mithraeum, and Late Usage, The Joint Expedition to Caesarea Maritima: Excavation Reports. (Lewiston, NY 1987) 25-38.

61 Bull and Blakely (above, note 60) 99-100. The specific numismatic evidence is small but a number of Roman colonial bronzes from Caesarea are included. One of the coins to which Blakely draws attention is from the first-second century AD and is smoothly worn. A second coin portrays Nero (AD 67/68), and a third portrays Elgabalus (AD 218-222).

62 Excavations of this area have taken place between 1997-2000. For a discussion of the Herodian foundation walls in LL 1, see “Combined Caesarea Expeditions: Areas TP and LL in the 2000 Excavations Season,” above, note 52. In the field report walls 1402 and 1411 in LL1 were found to be Herodian in date. Byzantine warehouse walls 1266 and 1217 were built on the Herodian foundations. It is the conclusion of the 2000 field report that the lower foundations were Herodian and that they had supported a Herodian warehouse. Previous excavations took place in 1975, 1976 and 1979. Lee I. Levine, Ehud Netzer. Excavations at Caesarea: 1975, 1976, 1979 — Final Report, Quedem: Monographs of the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 21 (Jerusalem 1986).

63 BJ 1.415; AntJ 16.136-138; AntJ 15.331.

68 Porath (above, note 57) 25, note 17.

69 Porath (above, note 57) 15-27; John H. Humphrey, Retrospective (above, note 9) 120-129.

71 There are several arguments pro and con for a Herodian date for the walls. See the arguments in Caesarea Papers (above, note 9) in the following articles: Avner Raban, “In Search of Straton’s Tower,” Caesarea Papers, 7-22; Duane W. Roller, “Straton’s Tower: Some Additional Thoughts” Caesarea Papers, 23-25; Jeffrey A. Blakeley, “Stratigraphy and the North Fortification Wall of Herod’s Caesarea,” Caesarea Papers, 26-41; T.W. Hillard, “A Mid-1st c. B.C. Date for the Walls of Straton’s Tower?” 42-48. See also: Avner Raban, “The City Walls of Straton’s Tower: Some New Archaeological Data,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 268 (1987) 71-88.