Epitaphs and Tombstones of Hellenistic and Roman Cyprus

II. Survey of Tomb Marker Types

Page 2

Tomb markers became much more common during the Hellenistic and Roman periods on Cyprus, but their presence is noted during the Archaic and Classical eras.3 Pre-Hellenistic tomb markers tend to be στῆλαι, many of which are plain limestone or sandstone slabs. Sometimes a simple painted fillet was “tied” around the στήλη. The most elaborate variety depicts the deceased, either seated or standing, alone or in variations of the farewell scene.4 Local limestone was employed for most of these figured στῆλαι, but others were of fine marble, imported as finished products.5 Two varieties of pre-Hellenistic funerary sculpture are known. Guardian lions are reported from cemeteries at Tamassus and Marion (later Arsinoe), some bearing epitaphs.6 A series of large-scale terracotta statuary was peculiar to the Marion area during the Classical period.7 Subjects include seated men and women, banqueters, mourners, mistresses and servants, and mothers with children, themes that persist in later funerary στῆλαι and statuary. Epitaphs consist of the name of the deceased in the nominative or the genitive, often accompanied by a patronymic.

During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, tombstones of various types marked the locations of tombs. Many of their epitaphs are still legible, naming the occupants who once lay below. Sepulchral monuments identified tombs externally and internally, indicating that tomb locations were not intended to be concealed. Placement divides tomb markers into external and internal monuments, according to when the viewer would encounter the particular type. Cuttings, some with στῆλαι still in situ, confirm that these monuments stood over tomb chambers. Other types, such as the ubiquitous cippi (see below), were similarly placed. Plaques bearing inscriptions could be housed above or beside doors to identify the occupants to the passerby. Freestanding statuary, the rarest class of externally placed memorials, also could stand above the tomb. Other markers identified specific burials within tombs. These often took the form of plaques, but epitaphs could be engraved or painted directly on the wall near particular loculi or arcosolia.8 Individual sarcophagi could be similarly inscribed.

The cippus was the tomb monument par excellence of Roman Cyprus, with over 690 published examples. It is freestanding and relatively simple in shape, essentially a short columnar altar.9 The base is clearly delineated, rising into a narrower shaft and broadening again to a capital proportionately smaller than the base. Moldings and engraved bands emphasize these three elements. Further bands sometimes divide the shaft into two or three panels. Cippi are furnished with two circular or rectangular cuttings, one in the upper surface, the other directly opposite in the base.

Local workshops mass-produced the cippi. The cuttings in the top and base served to fix the cippus for shaping on a lathe. The moldings were also cut in this manner, confirmed by overlapping lines creating the panels. Any additional sculptural decoration was added subsequently, the moldings refined, and ultimately plaster and paint applied. cippi remained blank in readiness for use, awaiting the final inscription at the behest of the purchaser. Aupert cites several unfinished and uninscribed cippi from Parekklisia in Amathus District, which he attributes to a nearby workshop.10

Shape and overall proportions vary somewhat with district. cippi in Tamassus and Citium Districts can be quite slender, almost attenuated and deceptively tall, while those from Curium and Amathus Districts tend to be rather fat. Such differences reflect local workshops, or perhaps the tastes of the clientele. Many cippi are relatively plain, with moldings providing the only decoration. Some cippi retain patches of white plaster, and traces of red paint pick out details, particularly moldings and inscriptions. A singular instance of engraved decoration, a pair of upraised forearms and hands, is attested at Klerou in Tamassus District.11 The motif, which could be interpreted as a gesture of prayer or entreaty, is characteristic of Asia Minor as is the type of epitaph employed.12

Relief ornamentation, requiring greater care and expense, occasionally decorates cippi. Swags of foliage or wreaths sometimes adorn the shafts, perhaps in imitation of real garlands draped over cippi as offerings.13 Garlands were common funerary tokens throughout the Mediterranean, and routinely sculpted on Roman sarcophagi and altars. Wreaths can be interpreted as victory emblems, symbolic of triumph over death. Portraits carved into the bodies of cippi involve great effort, and were correspondingly rare. These high relief images probably depict the deceased, and examples include representations of a beardless youth, a young woman, and a bearded man.14 In this instance, a characteristically Cypriot funerary monument has been combined with the archetypal Roman funerary portrait. Portrait-bearing cippi are confined to central and southern Cyprus, specifically to Citium and Tamassus Districts, paralleling the distribution of free-standing portrait busts discussed below. Finials in the form of large stylized pinecones were sometimes inserted into the upper surface of the cippus, making secondary use of the extant cutting.15 The hidden seeds may have symbolized rebirth, and Mitford comments that stone pinecones do not fade like flowers and would act as perpetual offerings.16

Egalitarian monuments, cippi served the middle class and wealthy alike. Numbers indicate that they were the preferred monument, in the clear majority among Roman tombstones on Cyprus. Expensive marbles and sculptural decor permitted elaboration to the satisfaction of wealthier clients, while plainer versions in local stone sufficed for the less well-to-do. All cippus epitaphs are in Greek. Over 80% belong to the common ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula, with variants remaining infrequent, but the presence of ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ is notable in Tamassus District. Men outnumber women two to one. These monuments usually honor single individuals, but sometimes as many as four. In such cases, the cippus might commemorate members of the same family or could reflect happenstance appropriation. Occasional Christian references occur, in the form of tilted Xs or the substitution of ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ for ΧΡΗΣΤΕ, with none assigned to a date later than the 3rd or early 4thc AD.17

As with στῆλαι, the most likely site for a cippus is the flattened area above the tomb chamber, as size and bulk renders it too large for placement within or before the chamber. In addition to functioning as tomb markers, cippi probably played a role in funerary rituals. The designation cippus or altar implies this second use, in all likelihood correctly. Garlands could be suspended from cippi, and the monuments girded with wreaths and fillets. The flat upper surface of the cippus easily accommodates flowers, vessels containing food or drink, and burning lamps, left on the occasion of anniversaries and festivals of the dead.18

The chronology for cippi is difficult to refine. The shape remains constant over a long period of time, and cannot assist in tightening the chronology. cippi are rarely associated with securely dated contexts; consequently, the best means of dating relies upon epigraphic criteria. The rough consensus attributes the beginning of cippi to the end of the Hellenistic period, with their apogee in the 1st–3rdc AD, but not continuing beyond the 3rdc.19

Mitford observes that cippi are most common in the neighborhoods of Citium and Amathus, and to a lesser extent, Curium.20 He adds that they are rare in the northern Mesaoria, completely lacking in Paphos, Arsinoe, and western Soli Districts, with their absence in the north and the central massif a consequence of the lack of suitable limestone. While the outlines of this picture are correct, the details need to be modified.

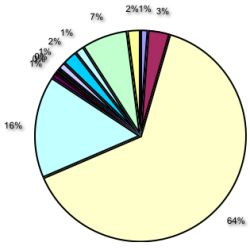

Figure 2: Distribution of cippi

Amathus, Citium, and Curium are certainly the major producers of cippi, with a distribution extending into their hinterlands. Inland, Tamassus District produced a substantial number of cippi, and Ledri itself also contributed a number. While the northern districts, Lapethus, Soli, Chytri, Ceryneia, Carpasia, and Salamis, were not as prolific, their efforts should be noted, and so should those of Paphos. Although limestone was the material of choice, sandstone and marble were also employed.

Cippi were the characteristic burial monuments of Roman Cyprus. Fairly plain and serviceable tombstones, they commemorated all classes, even resident foreigners. Materials and decoration tend to be restrained, but some elaboration was possible. Epitaphs offer minimal information regarding the deceased. These tombstones served as funerary monument and altar combined, placed above chamber tombs. Funerary altars are well attested throughout the Mediterranean particularly during the Roman period.21 No exact parallels for the Cypriot cippus can be found, but it is clearly related to types found in the Eastern Mediterranean. Asia Minor in particular ought to be noted as a source of cylindrical altars, including examples inscribed with the ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ formula type seen on some Cypriot examples, and others bearing depictions of garlands in relief.22 The closest parallel for the shape is found in late Hellenistic and Roman Rhodes; Rhodian altars are very similar in size and proportion to the Curium cippi, but with differences in the details of the capitals and epitaph formulae.23 Syrian funerary altars, in shape rough shafts, sometimes bear the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ simpliciter epitaph type seen in Cyprus.24

Columns rarely functioned as tomb markers in Hellenistic and Roman Cyprus; only ten have been published. All are quite plain, and consist of the shaft only, lacking base or capital. Epitaphs are in Greek, and follow the practices observed on cippi. The ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula is most common, with ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ occurring in Tamassus District. Most columns commemorate men, including Christians and a nobleman from Asia Minor, whose origin and status are indicated by his name, titles, and the use of the epithet ἩΡΩΣ.25 All column tomb markers have been dated to the Roman-Late Roman period, with the majority belonging to the 2nd-3rdc AD, coinciding with the floruit of the cippus. All originate in the proximity of major settlements, if not from the cities themselves, where column drums were readily available. Columns of Late Roman date may reflect partial abandonment of the site of provenance. Column tomb markers probably functioned in the same way as cippi, marking the tomb externally and serving as altars. The drums approximate the cippus in size and shape, and the formulae employed in the epitaphs of most of these monuments reflect those seen on cippi. Given these similarities, it is very possible that most of these columns were appropriated to secondary use as tomb markers. All were found in areas where cippi have been reported; perhaps there was no cippus to hand, and a column drum was used instead. From the scarcity of the type, it is apparent that this was not a usual method to mark tombs.

Στῆλαι are second to cippi in popularity. The 150+ στῆλαι follow canonical form, consisting of a rectangular stone slab taller than it is wide. The class is intended to stand upright, either fixed into a slot cut in the ground or into a base. Although the viewer was able to walk around the entire monument, decoration and inscriptions are generally confined to one side, the “front,” facing the passerby. The type appears in on Cyprus the Archaic and Classical periods, continuing into Hellenistic and Roman times, with epitaph and style determining date.

Many στῆλαι are relatively plain or topped with simple moldings or pediments. Unadorned rectangular στῆλαι appear to be rare during Hellenistic and Roman times; the most popular variety consists of a gently tapering shaft topped by a pediment. About one-third of published στῆλαι belong to this group, ranging from schematic to quite elaborate, consisting of a miniature rendition of the architectural original, complete with geisons, cornices, dentils, and acroteria. The type is a simple one, found outside Cyprus, and common in Egypt and Greece.26 Epitaphs are inscribed on the bodies of the στῆλαι, with red paint for emphasis.

Various elaborations of the pediment type are attested. Rosettes and a shield in the round respectively embellish two Hellenistic στῆλαι from the Amathus region, while a wreath surmounts the epitaph of a Roman tombstone from Citium.27 Painted decor was also an option. Red sashes appear on at least five Amathus στῆλαι, perhaps in imitation of actual fillets knotted around tombstones, during the first half of the Hellenistic period. This type follows a custom seen earlier in Cyprus, and parallels Hellenistic examples from Alexandria.28 Occasionally, pediments are the subject of sculptural elaboration, and include representations of rosettes and elaborate acanthus scrolls.29

Στῆλαι are well suited for the display of figural scenes, be they sculpted or painted. Figural monuments can be seen as a development of the pedimented type. The blank space on the shaft is given over to a scene, with the architectural elements serving as a frame. Sculpted στῆλαι begin during the Archaic Period on Cyprus, continuing through the Classical and into the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Several groups can be discerned among the approximately 50 sculpted στῆλαι reported.

The first of these groups belongs firmly to the late Classical tradition epitomized by Attic στῆλαι, continuing into the early Hellenistic period on Cyprus. Some of the στῆλαι bear sculpted groups, usually farewell scenes, while others portrayed individuals.30 A related series consisting of eight painted στῆλαι from Amathus bears scenes resembling their sculpted counterparts of the late Classical and early Hellenistic periods. All are made from local limestone, surmounted by pediments with acroteria, which are often offset by a painted egg-and-dart molding. The scenes are very classical in conception, with regards to subject, composition, and manner.31 Subjects include farewell scenes as well as solitary standing or seated figures similar to those seen on their sculpted associates. The painted στῆλαι belong to a narrowly defined series, limited in both chronological and geographical disposition. All known examples of this type from Cyprus were found at Amathus. Hinks dates the British Museum examples to the 3rdc BC, presumably on a stylistic basis. Hermary refines that date, adding that the στῆλαι clearly owe a debt to 4thc BC Attic sculpted predecessors, and should be dated to the first half of the 3rdc BC. Nicolaou dates the two surviving inscriptions to the early 3rd and to the 3rd-2ndc BC respectively.32 The genre did not endure, nor did it spread to other cities in Cyprus. While material indicates that the στῆλαι are local products, in style and subject they are akin to similar works of the early Hellenistic period from Alexandria, Macedonia, and Thessaly.33 The Cypriot στῆλαι probably imitate those from Alexandria, which in turn copy northern Greek works. The two preserved inscriptions commemorate foreigners, one from Kalymnos, the other a Babylonian. Nicolaou suggests that many of the ethnics cited on tombstones of this period attest to the presence of foreign mercenaries brought to Cyprus by the Ptolemies.34 Ptolemaic officials and their dependents residing at Amathus may have commissioned these painted στῆλαι, or perhaps members of the local upper class in imitation of Alexandrine custom.

In types ultimately descended from the old Attic models, the Hellenistic and Roman στῆλαι of a subsequent group feature single or grouped protagonists. Their subjects are not rendered in a purely Classical manner, since the subjects often stare boldly out at the viewer and are frontally posed as seen on Roman στῆλαι in Italy and the provinces.35 Twelve architectural στῆλαι framing single occupants are reported from around the island during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, concentrating in Amathus and Citium Districts. The niche and surmounting pediment are often quite rudimentary. Men and women are represented in equal numbers, often depicted standing, looking out at the passerby, and cradling a bird or piece of fruit in the hand; a few examples of soldiers also occur.36 Hairstyles, particularly during the Roman period, reflect current fashions. While the type usually represents a single person standing within a niche, pairs exist.37 A related type portrays seated subjects, usually a woman, but sometimes a couple.38 The στῆλαι are made from local limestone, and presumably were produced on Cyprus, an assumption which the sculptural styles support. The areas of Amathus and Golgoi are likely candidates for workshops in view of the numbers of στῆλαι found there and given the Golgoi sculptural tradition and the existence of cippi workshops near Amathus.

The banquet group is an elaboration of the Atticizing στῆλαι group, with 14 examples reported. In this type, the usual individual or farewell scene occupies the greater part of the στήλη surmounted by a second vignette.39 This second scene, contained within its own frame and sometimes crowned by a pediment, depicts a banquet, probably funerary in nature. One or more individuals recline on a couch facing the viewer, sometimes filling the entire scene. Often there are additional figures, either sitting or standing, and usually depicted on a smaller scale, indicative of servile status. The banqueters do not adhere to the Classical canon, possessing overlarge heads with their bodies in lower relief and more cursorily defined, which is characteristic of provincial work. The banqueting type seems to be confined to the areas of central and eastern Cyprus, specifically to Golgoi, Tamassus, and Salamis. Golgoi was home to a thriving sculptural school at this time, and could easily have produced στῆλαι of this type. The use of local limestone and the rather “naive” style also point to Cypriot manufacture. Tatton-Brown dates the beginning of the banquet scene type to the second quarter of the 5thc BC, and adds that it does not owe anything to similar slightly later examples from Greece.40 She assigns its combination with the larger figural panels to the Hellenistic period, continuing into Roman times. Around the time of this combination, the cast of the banquet expands beyond a single individual, often encompassing an entire family.

Sculpted στῆλαι very close in spirit to Roman funerary portraits seen in Italy and throughout the empire comprise a final group.41 The best- known example of this group, a στήλη from Tremithus, depicts a closely-knit group of parents and son surrounded by an elaborate architectural frame.42 Variations exist, with differences lying in the numbers of individuals represented and their sexes.43 A singular late example from Phasoulla dating to the 4thc AD depicts parents and their daughter in a flat schematic Syrian style and attests to the longevity of the type.44 All of these romanizing portrait reliefs are made from local limestone. For the most part, they originate in Tremithus and Golgoi in central Cyprus, products of local sculptural workshops. Scholars date these portraits to the 1stc AD, associating them with freestanding portrait busts described later in this article. The Phasoulla στήλη is an isolated example, but may be evidence for other Late Roman examples that have not survived. These στῆλαι and the related portrait busts should not be considered portraits in the true sense. Rather than representing specific individuals, these monuments depict idealized images of the deceased.

All στῆλαι epitaphs are in Greek. Most of the Hellenistic epitaphs follow the simple nominative, as do a few of the Roman examples. During the Roman period, as seen on cippi, the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula with its usual variations is the most common type found on στῆλαι. Metric epitaphs, the third most frequent formula on στῆλαι, straddle both periods, appearing equally in each. Epitaphs reveal that στῆλαι commemorate over twice as many men as women. Nicolaou ascribes the prevalence of ethnics attached to men’s tombstones during the Hellenistic period to the presence of Ptolemaic mercenaries, and this seems quite plausible.45 Age is cited relatively frequently, more often for men. Στῆλαι epitaphs are also rather informative with regards to professions. The percentage of military men supports Nicolaou’s supposition regarding the presence of mercenaries. To be noted, particularly for such a large class of monuments, is the complete absence of Christian references. This is partially a consequence of the rarity of στῆλαι in Late Roman times, but scarcity did not inhibit Christian references on cippi.

Evidence for the placement of these funerary στῆλαι includes the following. Incorporated into the epitaphs are such phrases as ΕΝΘΑΔΕ ΚΕΙΜΑΙ and ΕΣΤΙ ΤΟ ΣΕΙΜΑ, which imply that the deceased lies nearby and that the tombs are likewise in the proximity of the στῆλαι. While most στῆλαι are not found in situ, some retain their bases, while rectangular cuttings to house στῆλαι can still be seen in the bedrock directly above tomb chambers at Amathus and Curium.46 Στῆλαι may have been placed outside chamber entrances, but they were too large to be accommodated within the chamber proper. The most likely site for these στῆλαι remains the surfaces above the tomb chambers, similar to the placement of cippi. As with cippi, garlands and sashes might have been draped over στῆλαι during funerary rituals.

Στῆλαι are particularly common in the vicinity of Amathus and Citium, but are found throughout the island, particularly at the district seats, although not in large numbers. Στῆλαι appear earlier than cippi and continue in use alongside them, albeit in decreasing quantities. Dated by a combination of epitaph and style, they occur continuously throughout the Hellenistic and Roman periods, maintaining an earlier tradition. Two peaks of occurrence, during the early Hellenistic (3rdc BC) and the high Roman (1st-3rdc BC) periods, should be noted.

Freestanding sculpture comprises another class of funerary monument. Sculpture was displayed on the interior and exterior of tombs. Foreign influences provide the inspiration for a custom that was never widespread, though there are Classical precedents on Cyprus, particularly at Marion. It is not always easy to ascertain whether a particular sculptural work was funerary in nature as very few examples have been found in situ. In some instances, monuments have been identified as funerary based on foreign parallels, while others have been retrieved from known cemeteries. Two types are attested: guardian lions and portraits.

Two particularly fine examples of lions from necropoleis have been published, one from Nea Paphos and another from Curium.47 Both lions crouch, preparing to spring, and are made from fine imported white marble. Vermeule attributes the Nea Paphos example to an Attic master dated to just after 325 BC, and believes the Curium work to be contemporary or perhaps slightly earlier (340-320 BC), also an import.48 Clearly these two monuments are of considerable intrinsic worth, and suitable to adorn the funeral monuments of wealthy patrons. Such large-scale sculpture would require a substantial base like the built bases discovered at Amathus and Curium.49 Lions functioned as guardians, intended to ward off intruders from the tombs they defended. They were traditionally appropriate guardians and can be seen protecting Roman tombs in Asia Minor.50 Lions are also attested on earlier funerary monuments in Cyprus.51 Although the two monuments under consideration are clearly imports, local tradition was receptive to their subjects.

The largest body of freestanding statuary consists of portraits, including busts and two full-length statues. The busts are related to the portraits incorporated into cippi and relief στῆλαι previously discussed. Twenty-six portrait busts of men and 12 of women survive.52 Men are depicted as beardless, ageless in aspect, with wreaths of rosettes or flowers binding their short hair. Women appear ideally young, usually veiled but sometimes bare-headed, and adorned with jewelry, including fillets peeping out from under their veils. The veils and fillets of the women and the wreaths of the men may reflect the “participation” of the deceased in funerary rituals marking their burials, stone counterparts of gold funerary diadems and wreaths binding the brows of their corpses. Nearly all of these portrait busts are made from local limestone, and traces of coloured paint survive. Only one portrait is accompanied by an inscription; consequently dating of the portraits is primarily based upon sculptural style and the coiffures of the subjects.53 The consensus assigns the main body of the limestone busts to the late 1stc BC — 1stc AD.54 Most originate in the area of Golgoi and share a common style. The region possesses a steady supply of workable limestone, and was home to known sculptural workshops.

These busts could have been displayed in various manners. All face front and their backs were often left plain, a fact suggesting that these busts were intended to be viewed from the front. Possibly they were housed in niches on tomb exteriors; perhaps incorporated into the facades. Equally probable is the idea that they were placed within the tomb. There may be some ritual function attached to these portrait busts: fire blackening on some could be a consequence of oil lamps left lit nearby or of incense or food burnt in front of the portraits.55

The association between portrait busts and tombs is well documented across the Roman Empire. The style of Cypriot sculpture during the Roman period has not been well studied, but on Cyprus this form of portrait bust appears to be a Roman phenomenon. Adopted in imitation of the Roman custom, it was either transmitted directly from Italy or via the other provinces.56 The production of portraits appears concentrated in the central part of the island during the early Roman period. Since only one spurious inscription survives, there is no indication as to whom these portraits commemorated. While the portraits are local products, the patrons may have been foreigners in residence on Cyprus. Equally probable is the idea that they were made for local inhabitants adopting a common Roman custom. The cost of such a monument would have resided in the artistry, and was probably within the grasp of the middle classes, though the taste may have been confined to the romanized upper classes.

Full-length depictions also occur in Cypriot funerary sculpture of Hellenistic and Roman date, albeit rarely.57 Two examples of mistress-and-maid groups are known, one from an excavated context at Arsinoe. The Arsinoe example stood on a platform above the tomb in association with a group of terracotta funerary sculpture, and is dated to ca. 325 BC, presumably on kinship to Attic στήλη reliefs.58 The motif recurs in a large-scale sculpture from Golgoi dated to the late 1stc AD, signed by a local artist, Zoilos of Golgoi.59 The subject matter would be appropriate for a woman of some means, a “society matron,” as it was among the earlier Attic funerary στῆλαι.

In addition to freestanding monuments, the Cypriots employed inset plaques and blocks. Inscribed or painted epitaphs performed a similar function. Some were clearly intended for tomb exteriors where they were visible to passersby. Others identified individual burial places within a tomb, such as arcosolia or loculi.

Stone plaques were fixed to exterior facades or interior walls of tombs, with over 70 examples reported.60 In form, they are thin slabs, usually rectangular but sometimes square in shape. As a class, plaques are very plain, relying upon fine finish or expensive marbles for effect, with paint sometimes emphasizing the lettering. Ivy leaves punctuate a few epitaphs, while simple moldings constitute the borders of others.

All but three epitaphs occurring on plaques are in Greek, and one of these plaques is a bilingual monument. The most frequently encountered formula among the Greek epitaphs is the metric type, accounting for over 30% of published examples. At the other end of the spectrum, the simplest types of epitaph also occur, particularly the nominative (over 20%), with ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ ranked as the third most popular type (over 15%). The three Latin epitaphs follow proper Roman conventions, employing the Dis Manibus, HS Est, and Monumenti Causa formulae.61 Among the deceased, men appear twice as often as women. Several of the dead bore Roman names, while foreign ethnics describe others. Ages at death are given on a number of plaques. Two Latin examples specifically refer to class, including a freedwoman and an equestrian. Professions are mentioned for an unusually large proportion of the honorands of these plaques, an indication of their relatively high social status. Several plaques identify Christians.

Plaques were popular throughout the Hellenistic and Roman periods. During the Hellenistic period, they are most frequent during the 3rd-2ndc BC, decreasing in the 1stc BC. There is a resurgence during the Empire, remaining steady in the 1st-3rdc AD. Not many tombstones of any type are preserved for the Late Roman period, but plaques persist.

Although no plaques were found in situ and only a few remained in proximity to their original settings, there are various clues to their original placement. Depressed rectangular panels above chamber tomb doors of an appropriate size and depth to house plaques indicate that at least some were affixed to the facades. This practice is well paralleled, particularly in Italy, and the epitaphs themselves confirm such a placement.62 Metric epitaphs sometimes directly address the passerby as ΞΕΙΝΕ, ΠΑΡΟΔΕΙΤΑ, or ΟΔΟΙΠΟΡΕ, while others refer directly to a “monument,” a construction found above a tomb rather than inside it, and along with it, the identifying plaque. Other plaques were placed inside a tomb, identifying individual occupants in the same way as epitaphs painted or inscribed on walls and sarcophagi. Such plaques were set into a tomb wall, particularly when the structure was equipped with many loculi.63 Others were attached to sarcophagi.

Nearly 95% of the published plaques have a provenance, representing every district except Carpasia.

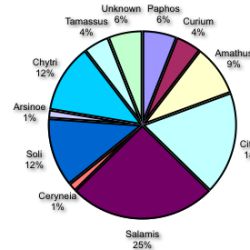

Figure 3: Provenance of published plaques

Salamis District produced the largest number of plaques (26%), all associated with its capital. Citium District, the second largest producer of funerary plaques (19%), assigns its majority to the district seat and one to Idalium, an ancient city-kingdom. Soli District should be considered the third largest producer of funerary plaques (12%), with all coming from the district seat. All plaques from Amathus, Tamassus, and Curium Districts derive from the respective district seats, as do the single examples from Ceryneia and Lapethus Districts. Paphos District has produced 5 plaques, 3 from Nea Paphos, and isolated examples from Peyia and Pissouri, the former a major settlement. Chytri contributed 8 plaques, but as 7 derive from the same tomb, they should really be considered as a single occurrence.64The only published example from Arsinoe District comes from Steni, which is not a major settlement. The distribution of funerary plaques clearly centers around district seats. The high incidence of imported marbles, associated with the metric epitaph type, both forms of display, indicates that the plaque was favored by the well-to-do, both Cypriot and foreigner.

Another category of tomb marker consists of epitaphs inscribed on stone blocks, with 14 examples preserved.65 These blocks are of the type employed in building construction, differing from plaques in their thickness but not necessarily in their width or height. Like the columns, this type does not constitute a large group. Blocks may have been ad hoc substitutions for plaques, much in the same way that columns replaced cippi. Alternatively, they could have been incorporated into monumental bases for the display of funerary sculpture or into the architecture of the tomb itself. None have been found in situ. The placement and function of blocks probably did not differ substantially from those of plaques. Only two blocks bear any sort of incised decoration, consisting in both cases of a single motif, a simple cross and an ivy leaf marking the end of one line.66

Twelve examples bear epitaphs in Greek, while two are characteristically Latin. The Greek epitaphs vary widely in their choice of formula. Epitaphs of the metric type adorn four blocks, making this the most frequent variety. Four follow variations of the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ type seen so frequently on cippi. Two opt for the simple nominative. An epitaph from Vitsadha in Chytri District is not only inscribed in Latin, but follows a characteristically Roman formula, indicating that the deceased was Roman.67Several eastern ethnics occur among the Greek epitaphs. With one exception, the blocks commemorate men. In the exception, the epitaph states that a man hired an architect to build a monument -- a heroon, a term used in Asia Minor -- for his wife and daughter, into which it is presumed this block was inserted.68 Three men followed a military profession: one a Ptolemaic mercenary, the others Roman soldiers; a doctor and a deacon are also present. Four epitaphs commemorate Christians.

The blocks are equitably distributed across a very long span of time, from the beginning of the Hellenistic period into Late Roman times. In provenance they are more confined, with all except two coming from major cities on the south coast and their immediate vicinities. Inhabitants of these cities possessed the funds to commission elaborate tombs or freestanding sculptural monuments to be placed above their tombs, and these tombs in turn incorporate inscribed blocks in their facades or monument bases. Epitaph evidence, including the use of metric epitaphs and pertinent personal details, points to patrons of high status, as does the presence of marble. Proximity to cities also provided access to construction materials for recycled use as funerary markers. One Christian epitaph from Palaipaphos is inscribed on appropriated material, with earlier text on its second side.69 At the late date of this monument, areas of Palaipaphos had been abandoned, giving the makers of tomb monuments a ready supply of scavengeable material.

The most basic means of identifying the dead was to inscribe or paint the epitaph directly onto the walls of the tomb near the place of deposition, and is seen throughout the Hellenistic and Roman Mediterranean. Reports mention only a dozen such epitaphs, but it is very likely that many more once existed, and have faded with the passage of time.70 Some are placed on the walls of the tomb near the entrance, perhaps naming the owner or builder of the tomb. More often they mark an individual burial place, such as a platform, loculus, or arcosolium and identify the occupant, or at least one among several – probably the original burial. Red paint is often used to enhance inscriptions, and sometimes a tabula ansata or other device framed the epitaph.71 The epitaphs are all in Greek, generally consisting of text only. The type favors the genitive (4 examples), emphasizing ownership of a specific burial place, with two epitaphs following the ΧΑΙΡΕ simpliciter formula, and others the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula. These brief epitaphs do not provide much information beyond the names of the deceased. Eight examples commemorate men; only one belongs to a woman. Four sites are represented: Nea Paphos, Peyia, Carpasia, and Ceryneia, with examples dating to the Hellenistic to Late Roman periods.

The simplest way to identify the deceased buried inside a sarcophagus is to label the container itself, a custom widely paralleled throughout the Mediterranean.72 Inscribed plaques sometimes performed this function, but it would have been easier to inscribe the epitaph directly. Sarcophagi were often reused, but given the care expended on the epitaphs, the inscriptions probably referred to the original occupants. The majority of sarcophagi found in Cyprus are uninscribed; if the occupants were identified, it was in paint long since disappeared. Ten sarcophagi with epitaphs inscribed on their bodies or lids and a plaque have been published. Placement on the “front” provided the best visibility. Framing devices occur, such as tabulae ansatae and elegant moldings. The sarcophagi vary in their materials. Five are marble, pointing to an origin outside of Cyprus, such as Greece or Turkey, while others are made of local limestone. Sarcophagi were costly, as emphasized by the sculptural decoration on several. The manufacturing workshops left the epitaph panels blank, to be inscribed according to the wishes of the purchaser.

The epitaphs are all in Greek. There are four metric epitaphs, including two Christian curses. Nominatives account for four epitaphs, two occurring on the same monument. Two genitives are attested, and one Tamassus sarcophagus opts for the ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ formula. As with epitaphs inscribed or painted on walls, those inscribed on sarcophagi convey relatively little information about the deceased. Among the eight examples where the gender of the deceased is determinable, only one commemorates a woman and it was later reused for a man. One epitaph names the multiple occupants of a single sarcophagus. Only one sarcophagus indicates ethnicity; three belonged to Christians.

All of these inscribed sarcophagi derive from the necropoleis of large cities. The cities where these sarcophagi are found form a band down central Cyprus, from the north to the south coast: Soli, Chytri, Tamassus, Ledri, and Citium, with a single example from Salamis. This distribution may be a consequence of the small sample size, but it is significant that the major sites of Paphos, Curium, and Amathus are not represented. Inscribed sarcophagi are a subset of a larger group, and their distribution should be considered in relation to that of sarcophagi in general, particularly vis à vis imported marble sarcophagi. Inscribed sarcophagi range in date from the Hellenistic to the Late Roman periods, distributed somewhat evenly.

1 I. Nicolaou 1971, 14-5; Cassimatis 1973, 123-4; Tatton-Brown 1986, 439-53; Wilson 1970, 103-11. See also I. Nicolaou’s series “Inscriptiones Cypriae Alphabeticae” in the RDAC (=“ICA”).

2 The farewell scene is a motif with a long history in Classical funerary art, and depicts relatives bidding farewell to the deceased, often clasping hands.

3 For examples in Aegean and Pentelic marbles dating to the end of the Classical period, see Vermeule 1976, 47-8.

4 Buchholz 1978, 201; Buchholz and Untiedt 1996, 44; Nicolaou 1971, 11.

6 Arcosolia and loculi are receptacles cut into tomb walls, or built-in coffins. Loculi are essentially rectangular compartments opening off a chamber, while arcosolia lie parallel to the wall, consisting of a rectangular trough surmounted by a rock-cut vault.

7 Numerous examples of cippi are published in I. Nicolaou, “ICA.” Archaeologists of the 19thc were the first to apply the term cippus to these monuments, implying that they functioned as altars. More conventional Latin terms for tombstone include monumentum and lapis, but Horace uses cippus (Satires 1.8.12). The cippus is also employed on Cyprus for dedications to the Θέος (\Υψιστος, Aupert and Masson 1979, 380-3; I. Nicolaou, “ICA XXXII, 1992,” RDAC (1993) 223. The only connection appears to be in function as an altar. For information on this deity, Kraabel 1969, 80-93.

9 I. Nicolaou, “ICA V, 1965,” RDAC (1966) no. 5.

10 For a discussion of the ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ formula type, see Section III of this article. MAMA 5 (1937) 109-09 no. 225; SEG 26.1429, 2nd-3rdc AD.

11 Cesnola 1885, 146.1151-2, 147.1162; Gunnis 1936, 314; I. Nicolaou, “ICA IV, 1964,” RDAC (1965) no. 1; Mitford 1980, 1374.

12 Cesnola 1885, 148.1173-4; 1903, Suppl. no. 20; 1877, 436, no. 105; Buchholz and Untiedt 1996, pl. 55c; K. Nicolaou 1976, 293.

13 Cesnola 1877, 54; 1885, 121.882-91. I. Nicolaou 1971, no. 41a; “ICA II, 1962,” RDAC (1963) no. 5.

16 Mitford 1980, 1374; Mitford 1990, 2203.

17 Mitford assigns the beginning of the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula to the early years of the 1stc AD or perhaps to the second half of the 1stc BC, and on that basis dates the cippus, while the absence of letter forms characteristic of the middle to late 3rdc AD indicates their demise before that date (Mitford 1980, 1374). I. Nicolaou assigns the majority of cippi, those bearing the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula, primarily to the 2nd-3rdc, occasionally as early as the 1stc AD, while recording the smaller group engraved with ΧΑΙΡΕ simpliciter as late Hellenistic (see “ICA”). During the course of the Department of Antiquities’ excavation of the Amathus cemetery, 31 cippi were found in association with tombs. Nicolaou finds that the burial gifts confirm the dates assigned on the basis of the inscriptions, but since these tombs were in use from the Archaic period onwards, it would be difficult to contradict her epigraphical dating (I. Nicolaou 1991, 207). Aupert prefers a slightly earlier date for these tombstones, finding the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ variety as early as the Hellenistic period, with a floruit about a century earlier than Nicolaou’s, in the 1st-2ndc, continuing into the 3rdc AD (Aupert 1980, 237- 58).

19 Kurtz and Boardman 1971, 237, 301; Toynbee 1971, 253-4.

20 Åström 1968, 167-9; Kurtz and Boardman 1971, 301; SEG 7.715, 721, 723, 726-7, 736, 747; 14.798-9, 802, 805; 17.606-7; 26.1420-1, 1423, 1426-7.

23 I. Nicolaou, “ICA III, 1963,” RDAC (1964) no. 9.

24 Breccia 1912, 1:23; Kurtz and Boardman 1971, 218ff.

25 I. Nicolaou, “ICA XIII, 1973,” RDAC (1974) no. 3; 1971, no. 40; Hermary 1987, 71-2.

26 Hermary 1987, 73. For Alexandria, Breccia 1912, 2:pl.XXXIII.38.

27 Mitford 1950a, no. 22; Hermary dates the pediment to the late Classical or early Hellenistic, but the vegetal ornament appears to be more at home in the Roman period (Hermary 1987, 71).

28 Vermeule 1976, 50; Cesnola 1885, no. 104.629.

29 Hinks 1933, 5-6; Hermary 1987, 72-5.

30 I. Nicolaou 1967, 19 no. 7, 28 no. 36.

31 See Hinks 1933, 6 no. 9; Breccia 1912, 1:6-22, pls. XXII-XXXIII; Kurtz and Boardman 1971, 235, 302; also Tatton-Brown 1985, 67- 8.

33 Kleiner 1992; Toynbee 1971, 246-50; Kurtz and Boardman 1971, 220-35; Breccia 1912, 1:2-6; Breccia 1912, 2:pl.XX-XXI; Muehsam 1953, 55-113.

34 I. Nicolaou, “ICA XXXI, 1991,” RDAC (1992) no. 8; Karageorghis 1960, 269; Karageorghis 1966, 333-5; Cesnola 1885, no. 104.634; Hogarth 1889, 103; Buchholz and Untiedt 1996, pl. 56a,b,d; I. Nicolaou 1961, 407. For soldiers, see Masson 1977, 322; Cesnola 1885, no. 138.1031.

35 e.g. I. Nicolaou 1961, 406; Cesnola 1885, 126.917.

36 e.g. Cesnola 1885, nos. 104.633, 121.892, 122.906; Caubet 1977, no. L.1.

37 e.g. Cesnola 1885, nos. 121.897, 128.922; Caubet 1977, 172-6; Tatton-Brown 1986, 439-53.

38 Tatton-Brown 1986, 443-5; also Kurtz and Boardman 1971, 234.

39 Particularly the Republican and early Imperial portraits (see Kleiner 1992).

40 Dated early 3rdc BC by Vessberg and Westholm (1956, 84); dated c280 BC by Vermeule (1976, 54); Tatton-Brown prefers a 1stc AD date, which is preferable (1985, 61). The στήλη could even date later.

41 e.g. Hogarth 1889, 39; Masson 1977, 322; Cesnola 1885, nos. 121.894, 899, 902, 128.1033, 141.1054; Ergüleç 1972, 31.

42 The στήλη was found at Phasoulla, near Amathus (Karageorghis 1976, 846) and clearly resembles Syrian works.

44 Karageorghis 1984, 956; Parks 1996, 129.

45 Tatton-Brown 1985, 62; Karageorghis 1983, 910; Vermeule 1976, 35.

46 Master of the Peiraeus Museum No. 285 (Vermeule 1976, 35); Karageorghis 1983, 910.

47 Karageorghis 1981, 1021; McFadden 1946, 449-89.

48 Kubińska 1968, 61-3. For lions from the Greek world, Archaic and later, perhaps the most famous being that at Chaeronea, see Kurtz and Boardman 1971, 238-9, pls. 64-7.

49 Buchholz 1978, 201; Buchholz and Untiedt 1996, 44; Gjerstad et al. 1935, 324; I. Nicolaou 1971, 11; Myres 1914, 241-3.

50 Cesnola 1885, 144.1129-38, 145.1139-43, 1145-8; Myres 1914, 213; Bruun-Lundgren 1992, 9-35; Connelly 1988, 10; Albertson 1991, 17, 29; Cesnola 1882, 108; Karageorghis 1985, 96; 1989, 849, figs.153-4.

51 On the basis of this inscription, Cesnola identifies the tomb where the portrait was found as belonging to the Roman proconsul (Cesnola 1882, 109 n.1). Given Cesnola’s penchant for exaggeration, the evidence ought to be weighed with caution. Vessberg and Westholm state their doubts about the authenticity of the inscription and that it was in fact ancient (Vessberg and Westholm 1956, 99). In view of the superb quality of the surviving portrait, and that the tomb is identified as having belonged to the proconsul, surely his family would have been able to afford a properly inscribed epitaph rather than one roughly scratched into the base of the portrait.

52 Vessberg and Westholm 1956, 96, 99; Connelly 1988, 9-10; Bruun-Lundgren 1992, 20; Karageorghis 1985, 147; Albertson 1991, 24.

53 For examples of burning, Karageorghis 1985, 147; Bruun-Lundgren 1992, 12, 18-9; Connelly 1988, 9.

54 Bruun-Lundgren prefers to see the adoption of portrait busts on Cyprus as a reflection of contemporary Egyptian mummy portraits (Bruun-Lundgren 1992, 20-3). However, Cypriot portrait busts and Egyptian mummy portraits should be seen as contemporary responses to an empire-wide interest in portraying the deceased.

55 Gjerstad et al. 1935, 330; Cesnola 1885, 1032.

56 Vessberg and Westholm use the melon frissure coiffure and the hierarchical scale of mistress and maid to confirm the dating (Vessberg and Westholm 1956, 83-4).

57 The hairstyle is characteristically Flavian, and serves as the basis for the dating.

58 e.g. I. Nicolaou’s “ICA” series; 1971; Mitford 1950a; Mitford 1950b; Mitford 1971; Mitford and Nicolaou 1974.

59 I. Nicolaou, “ICA VIII, 1968,” RDAC (1969) no. 5; 1971, no. 37; Cesnola, 1903, 149.18.

61 I. Nicolaou 1968b, 76-84; I. Nicolaou 1971, 32.

63 e.g. Peek 1955, nos. 902, 1509; Mitford 1971, no. 147; I. Nicolaou, “ICA.”

64 Mitford 1950b, no. 18; CIL 3.215.

68 e.g. I. Nicolaou, “ICA”; Hogarth 1889, 11; Anastasiadou 2000, 336-7; Seyrig 1927, no. 12.

69 A tabula ansata is a common framing device used in epitaphs, and consists of a rectangular panel with triangular “ears” or handles flanking the sides.

70 I. Nicolaou 1967, no. 24; “ICA XII, 1972,” RDAC (1973) no. 4; K. Nicolaou 1976, 292; Mitford and Nicolaou 1974, no. 88; Mitford 1950b, no.9, 165, 169; Mitford 1950a, no. 21; Vermeule 1976, 73; Peek 1955, no. 1325; Buchholz 1973, 369.