Epitaphs and Tombstones of Hellenistic and Roman Cyprus

III. Survey and Analysis of Epitaph Types

Page 3

This section addresses epitaphs and the information they convey. The formulae followed in the epitaphs are grouped according to types, with a summary of the relevant monuments and deceased, accompanied by chronological and geographical distributions. The issues addressed concerning the deceased include gender, age, religion, ethnicity, class, and profession. Some epitaphs are unintelligible, others convey unintentionally bizarre meanings, while still others are not translatable but their meanings are evident. This is particularly true of the metric epitaphs. It may be that epitaphs were borrowed from “copybooks” by engravers not entirely sure of their meanings, and viewed by patrons equally unable to judge. Many of the simplest epitaphs, particularly those on cippi, include errors in spelling and grammar, reflective of a degree of illiteracy among the general populace, and confirming that these monuments mainly served a provincial middle-class clientele.

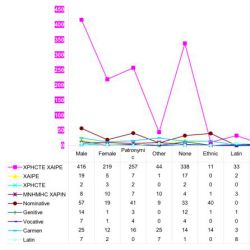

The largest group of epitaphs comprises nearly 80% of those published from Cyprus. The majority of this group adhere to the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula, with the remainder subscribing to one of two variants, ΧΑΙΡΕ simpliciter, and less frequently, ΧΡΗΣΤΕ simpliciter. ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ can be paralleled in Roman Asia Minor, particularly in combination with ΗΡΩΣ.73 ΧΑΙΡΕ simpliciter is a frequently encountered epitaph in the eastern Mediterranean, simple and effective.74 ΧΡΗΣΤΕ simpliciter appears in Syrian epitaphs.75

The most common among this category by far is the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula type, dominating Cypriot epitaphs in toto at 75%. The deceased is addressed in the vocative, described as good, and bidden farewell. The type commemorates men and women equally, in proportion to the ratio represented on tombstones (66 to 34%). Most often, no further information is given (53%), but patronymics occur frequently (40%), with grandfathers, metronymics, husbands, sons, and friends cited rarely (7%). Additional information concerning the deceased is equally infrequent, but includes ethnics (2%), adjectives (1%), profession (1%), and class (3 examples). Ethnics reflect mostly eastern Mediterranean origins. Roman names (5%) could point to an Italian presence, but given their frequent conjunction with Greek patronymics, they probably reflect the romanization of Cyprus. Adjectives are generic in nature, praising the virtue of the deceased. Rare references to the upper classes and freedmen confirm that cippi were essentially a middle-class monument.

Figure 4: The epitaphs on the cippi

Occasionally, the supplemental phrase ΟΥΔΕΙΣ ΑΘΑΝΑΤΟΣ appears, as seen in Judaea, indicating that the deceased was a Christian.76

The various distributions make the following apparent. ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ is seen most frequently on cippi (89%), appearing notably on στῆλαι (5%), but sporadically on other monument varieties. Geographically, the formula type is strongest in the Curium- Amathus-Citium-Tamassus stretch, paralleling the occurrence of cippi. In the northern Soli and Lapethus and the eastern Carpasia and Salamis Districts, the percentages are in proportion to the number of cippi, confirming the link between epitaph and tombstone types. The dating of the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula is essentially Roman, and closely tied to that of cippi.77

Some epitaphs of the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ class omit the descriptive adjective, reduced to ΧΑΙΡΕ simpliciter accompanied by the name of the deceased. This variation never becomes common (3% of all Cypriot epitaphs). With regards to gender, the percentages of men and women celebrated favor men slightly relative to overall ratios (72 vs. 28%), probably a consequence of the higher percentage of Hellenistic monuments present. As with the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ type, these epitaphs do not often reveal any information beyond the name of the deceased (54%), but patronymics occur (25%) and metronymics rarely. Adjectives praising the virtue of the deceased figure, while ethnics and Christian references are rare. (Fig. 4)

Like ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ, ΧΑΙΡΕ simpliciter appears most often on cippi (68%), followed by στῆλαι (14%). The remainder encompasses more monument types than its associate. ΧΑΙΡΕ simpliciter is the most popular formula in Ceryneia District and the western territories of Paphos and Curium. Occurrence is low in Citium, Salamis, Chytri, and Tamassus Districts, and is completely lacking in the northern districts of Arsinoe, Soli, Lapethus, and Carpasia. Nicolaou sees ΧΑΙΡΕ simpliciter as a forerunner of ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ, dating it to the late Hellenistic period.78Some cippi with this formula type date to this time, but others are Roman, ranging from the 1st into the 3rdc AD. If ΧΑΙΡΕ simpliciter is the precursor to ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ, it continues alongside its progeny.

ΧΡΗΣΤΕ simpliciter can also be considered an abbreviated form of ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ. Describing the deceased briefly as good, the type accounts for even a smaller percentage than ΧΑΙΡΕ simpliciter (<1%). With respect to gender, women are better represented than usual in this category, outnumbering men (60 to 40%), but that may be a consequence of the small sample size reported. Patronymics are often associated with the names of the deceased, though the names as often remain unencumbered. The epitaphs of this type provide no further information. (Fig. 4) ΧΡΗΣΤΕ simpliciter appears on cippi only, with the exception of a single στήλη. Geographically, the formula is confined to Amathus and Citium Districts. Reports do not discuss the dating of this type, but assign it to the 1st-3rdc AD in parallel with ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ and cippi.

A related but distinct formula group consists of the name of the deceased in the nominative, followed by the wish, ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ – for the sake of memory, sometimes abbreviated to ΜΝΗΜΗΣ. Although not common, its presence is significant (2% of all epitaphs). This variety of epitaph figures on a quarter of Tamassus District monuments, appearing sporadically in only three other districts. The formula is frequently seen in Asia Minor, and probably originates in that area.79 In Cyprus, it is more commonly associated with female burials than with men (50 vs. 40%). Patronymics are often mentioned (35%); followed by husbands for women or an absence of cited relatives; sons, friends, mothers, brothers, and grandfathers are rare. As in other types, Roman names do not guarantee the presence of Romans, but there is an example of an ethnic, as well as a Christian and some slaves. (Fig. 4) ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ is strongly associated with cippi and the related columns, with one example of a plaque and sarcophagus respectively. The linkage with cippi indicates that this formula type is contemporary with those tombstones and the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula. The examples of ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ from Asia Minor also belong to the 2nd-3rdc AD, confirming this chronology.

The epitaphs of a third category are very short and to the point. For the most part, they consist of the nominative, but the genitive and the vocative also function in this capacity, with no real meaningful distinction to be seen. These very basic means of identifying the deceased enjoyed a long history across the Mediterranean world.

Nominative citations of the deceased’s name occur in significant numbers among Cypriot epitaphs during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, as they did in previous times, forming the second largest class (9% of all epitaphs). Nominatives are most common in the early Hellenistic period, regaining strength in Late Roman times. In effect, the epitaph states, “this is X.” Male epitaphs are three times as frequent as female, partly a function of the large number of plaques in this class. It is also a consequence of date, since many of these epitaphs belong to the early Hellenistic and Late Roman periods, when fewer women are commemorated. Patronymics are most often mentioned (51%), followed by no cited relatives at all (44%); husbands and brothers, both associated with female burials, trail. This class of epitaph, despite its simplicity, is the most informative about the deceased. Over 50% mention an ethnic, more than 15% an age, while others identify professions or refer to the deceased as Christians. The ethnics are closely tied to the early Hellenistic στῆλαι associated with foreign mercenaries, which constitute a sizeable proportion of this formula category. The Christians belong at the other end of the chronological spectrum, to the Late Roman period. Age and profession are often mentioned with both of these groups. (Fig. 4) In contrast to the previously discussed formulae, nominatives figure most frequently on στῆλαι (38%) as to be expected from their concentration in the early Hellenistic period, followed by plaques (28%), with cippi in third place (19%). Geographically, their distribution favours those districts where cippi are not so common, appearing rarely where the cippus is the monument of choice.

The genitive formula type consists of the name of the deceased in the possessive, indicating that the burial place belonged to the dead person. Although less common than the nominative, its numbers are still significant (2% of all epitaphs). The sample is small, but very strongly favors men (93%). Generally, this type is confined to the name of the deceased, with patronymics occurring in 20%. Several epitaphs mention age, while others belonged to Christians. (Fig. 4) The genitive is usually seen where it would directly identify an individual’s burial place, such as a loculus or sarcophagus, directly inscribed into its surface or on a nearby plaque. Epitaphs on cippi and the single column in this group do not present as direct a connection with the deceased. Distribution of the genitive type follows that of labeled loculi and sarcophagi, occurring sporadically in certain coastal districts. With regards to date, the span of this type includes the entire duration of the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

Equally basic, the vocative formula names the deceased, as if addressing him or her. As with the genitive, numbers are small (about 1% of all epitaphs). Most of the deceased were male (88%). Patronymics and a lack of cited relatives are equally common (50% each). (Fig. 4) The vocative formula is not characteristic of a specific monument type, but is evenly distributed among several types. It is also scattered geographically, appearing for the most part in isolated instances, and skipping some districts altogether. Dates extend throughout the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

Metric epitaphs, or carmina, are the most elaborate found on Cyprus, with a long history in the eastern Mediterranean.80 Ranging widely from simple couplets to long, involved curses, all employ poetic devices and at least attempt to meet the requirements of meter. Generally, they praise the virtues of the deceased, bemoaning their premature demise. Many were probably not composed for a specific funeral, but had personal details inserted into a generic verse. It is a popular type (7% of all epitaphs), almost equaling the combined numbers of the simple type. Over two-thirds of the type celebrate men. Relatives of all varieties figure, particularly parents. Although patronymics occur, most parents are usually described in their capacity as mourners, left behind by the deceased. Often nameless, these parents may be a poetic device to render the epitaph more poignant, or they may have been the dedicants of the tombstones, as were other named relatives. While adjectives describing the virtues of the deceased were part and parcel of the type, other details are more personalized. Ethnics (24%) and age (31%) figure prominently, professions (17%) to a lesser extent, all lending themselves readily to the poetic form. (Fig. 4) Metric epitaphs are closely tied to monument type and geographical distribution. Approximately 50% occur on plaques and 25% on στῆλαι, whose shapes are well suited to longer epitaphs. Their strong presence in Salamis is closely associated with the frequency of marble plaques at the district seat, with the carmina and material clear indicators of status. Numbers suggest that the type was also popular in Paphos, Soli, and perhaps Citium Districts. Data are too limited to confirm trends in Ceryneia, Lapethus, and Arsinoe Districts, but metric epitaphs were not in favor in Curium, Amathus, Tamassus, and Carpasia Districts. Moreover, almost all metric epitaphs derive from district seats. With regards to date, they enjoy popularity in the early Hellenistic period, dropping off thereafter, and make a strong comeback in the High Empire during the 2nd-3rdc AD. Several Christian examples attest to the survival of the type into Late Roman times.

Latin epitaphs appear occasionally in Roman Cyprus, and their presence should be regarded as significant (1% of all epitaphs). These epitaphs follow well known Roman formats.81 The rarity of Latin inscriptions on Cyprus and the equally uncommon occurrence of typically Roman epitaphs suggest that these were meant to honour Romans, rather than locals adopting the custom of Rome. Two epitaphs are bilingual, the Greek and Latin portions employing equivalent formulae.82 Three quarters of the Latin epitaphs celebrate men. Dedicants are explicitly named, including a wife, a brother, fellow freedmen, and soldiers. All those celebrated in Latin epitaphs possess Roman names. Age, profession, and class ranging from freedman to eques are cited, as is common among Roman epitaphs. (Fig. 4) The majority of these epitaphs are inscribed on plaques, a typically Roman type. As one might expect, the distribution almost exclusively encompasses three of the most important district seats, Nea Paphos, Salamis, and Citium, where one would find Romans. All of these monuments belong to the period of the High Empire, bearing witness to the presence of Romans on Cyprus.

Analysis of epitaphs contributes the following conclusions concerning the deceased that they commemorated. On average, epitaphs province-wide indicate that tomb monuments were twice as likely to honour men as they were women. Examination within districts is best performed with Amathus, Citium, and Tamassus Districts, the three regions with statistically valid sample sizes, and it indicates some variation. Women were most often commemorated in epitaphs in Tamassus District (50%), followed by Amathus (33%), and then Citium (28%). Distribution across the districts is heavily weighted in favour of the district seats, but in Amathus and Tamassus Districts outside the district seats women are more often encountered on tombstones (43% and 44% respectively), while in Citium District, they are less frequent (25%). Over time, men are better represented during the early Hellenistic and Late Roman periods, with the numbers of women increasing during the High Roman era. Many men during the Hellenistic period may have been Ptolemaic mercenaries, while those from the Late Roman period were often church officials. The pax Romana seems to have encouraged mourners to commemorate their dead female relatives.

In contrast to gender, age at death is not often cited. When it occurs, it tends to be in metric or nominative epitaphs. In metric epitaphs, age emphasizes the sense of premature bereavement, as it is generally associated with children or young adults survived unnaturally by their parents. References to death prior to marriage also feature in this type of epitaph. When age is incorporated into epitaphs of the nominative type, it appears as a simple statement of fact. These seem to be true ages, spanning the entire range. Age is as likely to be associated with men as with women, in line with the overall ratio of the sexes.

Epitaphs sometimes convey information regarding social class, profession, ethnicity, and religious preferences. Class does not feature prominently in epitaphs, but references are about evenly divided between freedmen and the upper classes, with middle-class status not meriting mention. All are of Roman date, and all but one refer to men. About half derive from Latin epitaphs, whose formulae often allude to class. Freedmen and the upper classes were the most likely to stress class, one anxious to indicate that they were no longer slaves and the other proud of its inheritance. Adjectives beyond the conventional ΧΡΗΣΤΕ praise the upright moral character of the deceased, but remain rare, with men more likely to be so described. Probably a Roman trait, most occur on cippi or in metric epitaphs.

Ethnicity can be declared on tombstones in a variety of ways. Roman names, not uncommon (appearing in 6% of epitaphs), in most cases should be viewed as an indication of the romanization of the province, particularly at the large cities of Nea Paphos and Salamis. Latin epitaphs, however, commemorate Romans according to the traditional formulae of their homeland. Links with Asia Minor are reflected in the use of the ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ formula and the epithet ἩΡΩΣ.83 Ethnics are quite common, appearing in 8% of epitaphs, and more frequently associated with men. Often appearing in nominative formulae, they usually point to eastern Mediterranean origins. As many are men, when they date to the early Hellenistic period, the epitaphs likely refer to mercenaries.

Professions appear sporadically, and almost all describe men. Two major categories include soldiers and Christian officials. Both provide evidence for dating. Many soldiers are attested on early Hellenistic tombstones, a period of considerable military activity while the Christian references belong to the Late Roman period. Rare examples include a cook and a possible gravedigger.

Religious references are infrequent and belong to Christian burials. Earlier references are discreet, with crosses replacing Xs and ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ inserted for ΧΡΗΣΤΕ in cippus epitaphs and the occasional supplemental ΟΥΔΕΙΣ ΑΘΑΝΑΤΟΣ, a Christian formula paralleled in Judaea.84 Late Roman epitaphs are much more likely to commemorate men rather than women, and are more overt in their Christianity, utilizing psalms and mentioning church offices. No other religious affiliations occur on Hellenistic and Roman tombstones.

Relatives are often named in epitaphs. Some may be responsible for commissioning the tombstone in question, but often the cited family members identify the deceased much in the way of a modern surname.85 About half of the epitaphs do not mention any relative, with male and female deceased present proportionally. Epitaphs in the genitive tend not to designate a relative, while metric epitaphs usually refer to the parents. Parents appearing as pairs tend to be nameless entities in metric epitaphs, possibly a poetic device emphasizing the pathos of a premature bereavement, but also potential dedicants of the relevant tombstones. Fathers named in metric epitaphs, however, were more likely to have been dedicants. The ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ group and ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ epitaphs employ patronymics and other named relatives about half the time. Parents, particularly fathers, appear most often when a relative is cited. Patronymics in these epitaphs were intended to differentiate individuals bearing the same name as was the custom among the living, with men and women so identified in equal proportions. Grandfathers and great-grandfathers occur only in conjunction with a patronymic as a more precise identification of the deceased, rather than naming dedicants. Metronymics are rare and more likely to individualize men, but probably functioned in the same manner as patronymics. Spouses, however, are usually cited on women’s tombstones, sometimes in conjunction with patronymics. A named husband can identify the deceased in the same manner as a patronymic, but husbands, being younger than fathers, were more likely to outlive their wives and dedicate tombstones. Wives mentioned in epitaphs probably did not identify the deceased, but should be seen as the commissioners of the monuments. Siblings, very rarely mentioned, could function in either capacity. Friends and clients, when acknowledged on a tombstone, should be considered as responsible for its placement.

Epitaphs provide the only evidence that chamber tombs were family owned. Names held in common among several tomb markers found in a single context indicate that members of a single family were interred within the same tomb, confirming that at least some tombs belonged to individual families and that more than one tomb marker could be associated with a single tomb. Tombstones with multiple epitaphs served several individuals, sometimes related, based on the evidence of patronymics or explicitly stated kinship. In other cases links between tombmarkers are indicated by identical patronymics. At present there is no evidence for other types of organizational groups, such as the burial clubs known in Italy.

1 Åström 1953, 206- 7. Lattimore cites an example of Roman date from Larissa (Lattimore 1942, 282).

2 Butler 1913, 392; SEG 17.715, 26.1489, 1679; Breccia 1912, 1:xxxviii-xix.

3 Conteneau 1920, 49; SEG 26.1655.

5 Mitford finds the beginning of the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ type early in the 1stc AD or perhaps in the second half of the 1stc BC, which he links to the dating of cippi (1st- 3rdc AD) (Mitford 1971, 295 no.152; Mitford 1950a, 71; Mitford 1980, 1374; 1990, 2203). Aupert and Masson agree (1979, 361-89). I. Nicolaou dates inscriptions on the basis of letter shape, and usually assigns this type to the 2nd-3rdc AD when found on cippi. She places some στῆλαι bearing this type of epitaph as early as 50 BC, see “ICA.”

6 I. Nicolaou, “ICA XXVIII, 1988,” RDAC (1989) 145.

7 e.g. SEG 14.789, 798-9, 802, 805; 17.557, 605-8, 621, 667, 709, 721, 723, 726-7, 736, 747; SEG 26.1418, 1420-2, 1423-4, 1426, 1429.

8 Kurtz and Boardman 1971, 261-6.

9 Calza 1940, 263-368; for examples of DM epitaphs from Ostia, see CIL vol. 14, Suppl. 1-2; for examples from Rome, see CIL vol. 6, part 6, no. 2; vol. 6, part 7, no. 2.1.

10 Cesnola 1903, no. 149; CIL 3/4.12110.

11 I. Nicolaou, “ICA (III) 1963,” RDAC (1964) 197; idem, “ICA X, 1970,” RDAC (1971) 69; cf. Lattimore 1942, 97.

12 SEG 14.833; 17.780. Mitford indicates that this type of epitaph occurred on both Christian and Jewish tombstones, and was of Egyptian origin (Mitford 1971, 300). Lattimore also comments on an Egyptian variant (Lattimore 1942, 253), which is seen in one Curium epitaph.

13 For the most part, Cypriot tombstones provide too little information to permit reconstruction of family structure on the island. When only a mother is named, it may imply a female head of household, while patronymics were probably used as “surnames.” For examples of such studies, see Saller and Shaw 1984; Martin 1996.