Epitaphs and Tombstones of Hellenistic and Roman Cyprus

IV. Conclusions

Page 4

Tombstones and epitaphs existed on Cyprus prior to the Hellenistic period, but it is during Roman times that they come into their own. The prosperity enjoyed by the province under the empire may have provided the requisite conditions and funding for the proliferation of funerary monuments in this period. Tidy little cippi, with the occasional στήλη or statue interspersed, dotted the cemeteries, adorned with bright flowers or garlands, fillets, and offerings. Occasionally addressing passersby, their presence announced ownership of individual tombs, acting as visual statements of possession and identifying the deceased within. For the most part, epitaphs are statements of possession, farewell, or mourning; none convey any vision of the afterlife. A few tomb-markers bear curses, and were intended to protect the tombs. Epitaphs provide the best evidence to date that at least some chamber tombs served family groups. Chamber tombs were clearly marked; it is not certain whether cist tombs were also identified as no tombstones survive in association. cippi, columns, and στῆλαι could have stood above both chamber and cist tombs, while other types, for example plaques, were confined to chamber tombs. Tomb markers and funerary sculpture, interior and exterior, provided the focus for funerary rituals during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, both during the actual interment and during subsequent commemorations. Some tomb markers performed a function during funerary rituals, serving as altars or receiving offerings on behalf of the deceased.

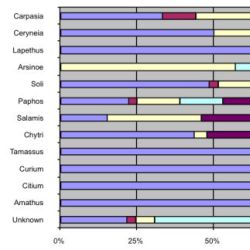

Among the 1020+ monuments recorded, the cippus is by far the most common tombstone type at 67%, followed at some distance by στῆλαι (15%); plaques (6%); sculpture (4%); and blocks, sarcophagi, columns, and inscribed/painted on tomb walls (each 1% or less). Upon closer inspection by district this picture varies.

Figure 5: Tomb marker types by district

cippi (22%) and tomb wall epitaphs (19%) are the most common tomb markers in Paphos District. Curium District is closer to the overall provincial mean, with cippi comprising the greatest number (66%), and στῆλαι, plaques, blocks, and sculpture less frequent. Amathus District also conforms to this norm, as is to be expected considering the large number of monuments recovered from the district, with cippi constituting 83% of its tomb markers, followed by στῆλαι (13%); plaques, columns, and blocks are rare, and funerary sculpture, wall epitaphs, and inscribed sarcophagi completely absent. cippi are also the most common tombstone type (65%) in Citium District, but the sculptural types, both στῆλαι and freestanding, occur in proportionally greater numbers than elsewhere on the island. Plaques, inscribed sarcophagi, and blocks are less common, while wall epitaphs and columns are absent. Among Salamis tomb markers, plaques are most frequent (33%), followed by στῆλαι (22%) and cippi (15%); inscribed sarcophagi are rare, and other types unrecorded. While few monuments are known from Carpasia District, its distribution is closer to the norm, with cippi most common, followed by inscribed walls, στῆλαι, and columns. cippi are also the most popular in Ceryneia District (50%), with columns, plaques, στῆλαι, and inscribed walls less common, and other types seemingly absent. Lapethus’ few reported monuments indicate that cippi are likewise in the forefront, succeeded by inscribed sarcophagi. cippi occupy first place in Soli District (48%), followed by plaques (24%) and στῆλαι (15%), while inscribed sarcophagi, columns, and sculpture are rare. Arsinoe, clinging to Classical tradition, prefers στῆλαι (57%), with single examples of blocks, plaques, and sculpture recorded. cippi (43%) and plaques (35%) occur in approximately equal numbers in Chytri District, with a few examples of inscribed sarcophagi, στῆλαι, and blocks; wall epitaphs, columns, and funerary sculpture are lacking. Tamassus District reverts to the usual distribution, cippi predominating (82%); στῆλαι, plaques, columns, and inscribed sarcophagi are rarer, occurring in similar numbers. Funerary sculpture, blocks, and wall epitaphs are absent.

The large numbers of cippi from Amathus District, and to a lesser extent Citium District, distort the overall picture. The events of 1974 have also greatly reduced the numbers reported from the districts now in occupied northern Cyprus, including Salamis, Carpasia, Ceryneia, Lapethus, Soli, and Chytri. Paphos and Arsinoe District finds are surprisingly slim, with no motivation readily apparent. But even assuming a recovery rate for Amathus and Citium at a half or even a third of what it has been, the following conclusions can be offered. cippi dominate by a wide margin, performing especially well in the Curium-Amathus-Citium stretch, extending northwards into Tamassus and Chytri Districts. They skip Arsinoe District altogether, and are proportionately restricted in Salamis District to the east. Στῆλαι are the second choice in the Curium-Amathus- Citium-Tamassus group, and also in Salamis District. They lead in Arsinoe District to the northwest, probably because of lingering attachments to Greece. Their popularity is reduced in the other northern districts of Carpasia, Ceryneia, Lapethus, Soli, and Chytri, and surprisingly, in Paphos District to the west. Plaques, in contrast, are more prominent in the north, particularly in Salamis and Soli Districts, but are third place in the Curium- Amathus-Citium-Tamassus block. Two minor groups, inscribed/painted tomb walls and funerary sculpture, center around particular areas, the first around Paphos and the second focusing on Citium District and its sculptural workshops.

Certain epitaph formulae are more closely associated with particular monument types than with others, resulting in parallel distribution patterns. During the Hellenistic period, στῆλαι bearing nominative epitaphs prevail across the island, succeeded to a lesser extent by στῆλαι of the ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ type. The popular ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ formula, so tightly tied to the cippus, dominates, particularly in the Curium-Amathus-Citium- Tamassus belt during Roman times. In contrast, plaques bearing metric epitaphs, often of marble, prevail in Salamis District.

Examination of tombstone materials also reveals some patterns, some linked to local availability, others to trade and class. Limestone is the most common material employed in funerary monuments at 68%, reflecting its accessibility. Sandstone ranks second overall at 20%, while marble is third at 11%. Within the individual districts, however, the picture varies from the province norm. Limestone dominates the Curium- Amathus-Citium-Tamassus-Chytri group, as well in Arsinoe, Carpasia, and Ceryneia Districts. Sandstone assumes second place within Amathus-Citium-Tamassus, as it does in Carpasia District to the northeast; third place in Paphos, Curium, Salamis, and Arsinoe Districts; but is completely lacking in Ceryneia, Lapethus, Soli, and Chytri, all northern districts and a consequence of geology. Marble is the material of choice for Salamis and Paphos Districts, and as frequent as limestone in Lapethus and Soli; second choice in Curium and Arsinoe; third choice in Citium, and completely lacking in Amathus, Tamassus, Carpasia, and Ceryneia Districts. Marble does not occur naturally on Cyprus, and must be imported. Marble is more prevalent in the west, north, and east, probably reflecting directions of overseas trade, with marble tombmarkers all deriving from district seats, good markets for the costly material.

By monument type, cippi and blocks are most commonly made of limestone (71 and 54% respectively), followed by sandstone (27% and 31%), and then marble (2 and 15%). Given the scarcity of marble cippi, it does not appear they were being made outside the island for the Cypriot market. It is possible that manufacturers pared down preexisting marble column drums or altars into the canonical cippus form. Marble and sandstone are equally common among στῆλαι and columns (7 and 33%), with limestone (87 and 33%) maintaining its dominant position. Marble is the material of choice for plaques and inscribed sarcophagi (76 and 67%), followed by limestone (22 and 33%) and sandstone (2 and 0%). The trade in marble sarcophagi is well documented, and those examples found in Cyprus traveled to the island as nearly completed works of art. Marble στῆλαι may have been imported as unfinished slabs to be carved locally or with their reliefs executed. Epitaphs were carved onto marble plaques as needed. With the exception of στῆλαι, marble is associated with Roman monuments, particularly with plaques. Marble, moreover, is concentrated at district seats, as is to be expected of an import, with distance a factor in its lack of penetration to Tamassus. Such cities provided the consumers for the costly material. Metric epitaphs are particularly associated with marble monuments, another sign of status.

Tombstone types can also be paralleled outside Cyprus. Funerary cippi are quite common in Italy and the eastern Mediterranean, particularly in Syria and Asia Minor, but the particular shape seen in Cyprus is characteristic of the island. Στῆλαι, however, are frequently encountered throughout the eastern Mediterranean in the forms seen in Cyprus, including the simple pedimented and the Atticizing varieties that precede and continue into the Roman period. Egypt has produced examples of στῆλαι similar to those from Cyprus, including the painted pictorial group. Funerary portraits found on the island are provincial interpretations of the Italian tradition, as are those in the other eastern provinces, notably Syria. Inscribed epitaphs on plaques, tomb walls, and sarcophagi appear in Italy and elsewhere. The formulae employed in epitaphs likewise are well paralleled, confirming that the island was attuned to the material culture of the east Mediterranean. The simple nominative and genitive types, as well as the ΧΑΙΡΕ and metric varieties appear in Greek epitaphs across the eastern Mediterranean, beginning in pre-Roman times. Other formulae are more restricted in their parallels. The Latin types have their origin in Italy, following Romans as they spread through the Mediterranean. Certain formulae, the ubiquitous ΧΡΗΣΤΕ ΧΑΙΡΕ, and the more restricted ΜΝΗΜΕΙΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ and (ΗΡΩΣ, find their best comparanda in Roman Asia Minor. ΜΝΗΜΕΙΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ, in one instance associated with a motif also from Asia Minor, is concentrated around Tamassus in central Cyprus, for reasons not yet understood. The relatively rare ΧΡΗΣΤΕ simpliciter is combined with epitaphs on Syrian funerary altars. The presence of foreign ethnics and epitaph types attests to foreigners living in the province, while the existence of Roman names indicates a degree of romanization. All of this agrees with information provided about other eastern Mediterranean provinces.

The evidence of monument type, decoration, and epitaph indicates that Cyprus belonged to the cultural κοινέ of the eastern Mediterranean. Overlying a strong core of Cypriot traditions are links with Asia Minor, Greece, Egypt, and Italy in particular. The strength of these ties varies in the different districts, perhaps drawing on earlier tendencies. Egyptian elements are particularly notable at Amathus, and perhaps at Paphos; those from Asia Minor especially in Tamassus District; Greek varieties perhaps in Arsinoe; while Italian elements are most frequent in the big cities. Egyptian influence was strongest at the beginning of the Hellenistic period, to be associated with the presence of Ptolemaic mercenaries and governing officials. Latin and Asia Minor elements are more characteristic of the Roman period, perhaps linked to commercial activities. Clearly Cyprus was far from being an isolated backwater, but should be considered a prosperous province receptive to external influences.

In addition to attesting to foreign influences and residents, epitaphs provide an interesting commentary on the society of Cyprus during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The island was home to a comfortable population, with a large middle-class sector. The tombstones indicate that at least some of the tombs were family-owned, and commemorated women more often in the Roman period than during previous or subsequent eras. Religious statements were confined to Christian references, remaining discreet and infrequent under the Empire, and only becoming overt with the official endorsement of Christianity in the Late Roman period.

The use of tombstones and epitaphs on Cyprus diminishes during the Late Roman period as is the case across the empire.86 Among freestanding monuments, cippi and sculpture disappear, while columns and στῆλαι are represented by a single example each. Plaques, blocks, and inscribed sarcophagi, however, continue in relatively constant numbers. Formulae tend to be confined to the simple nominative and genitive types, as to be expected when most epitaphs identified specific burial places. A few examples of metric epitaphs are attested, including a curse. The smaller numbers of tombstones may be a consequence of a change in rite, emphasizing the importance of the individual burial place or of a general reduction in the numbers of epitaphs empire-wide.